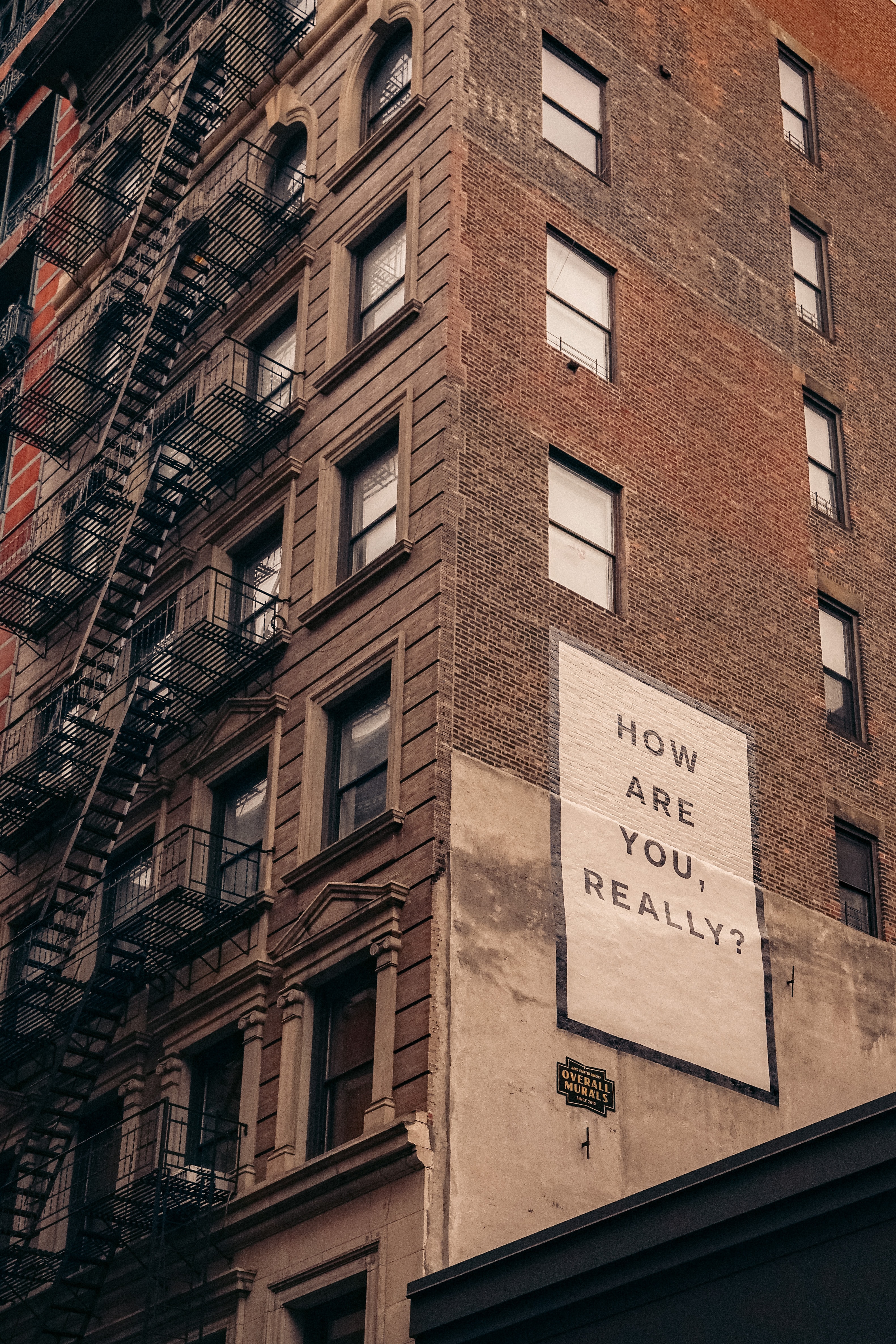

With the easing of COVID-related restrictions across the board, everyday life is starting to look more familiar. But is everything okay now? Probably not.

Statistics released by Lifeline last week show that daily call numbers have increased by about 25 per cent from 2019. That’s another 700 anxious and distressed people calling the help line each day, taking the average 24-hour total up to 3200.

And while it would be nice to think that, as Christians, our faith and confidence in Jesus will protect us from such difficulties, the truth is that no one is immune.

“Lots of people are feeling these discombobulated, bamboozled feelings,” says the Rev Dr Keith Condie, co-director of Anglican Deaconess Ministries’ Mental Health and Pastoral Care Institute.

“I want to promote calm, so one of the things I’ve been saying to people is that if you’re feeling like this, it’s a pretty normal outcome.

“We’ve all experienced significant losses. Some people have lost their jobs, they’ve lost financial security, but all of us – especially during the times of lockdown – had the loss of normal networks of social connection… a whole lot of these were taken away from us. Our normal routines were taken away from us and, I suppose, our sense of control.

“For some people who are vulnerable – who have either an existing mental health condition or are close to the edge, COVID-related stresses could cause real problems.”

“Our normal routines were taken away from us and, I suppose, our sense of control.”

Psychologist Bronwyn Wake, who works at St Andrew’s Cathedral School, uses the example of a “cup full of stress and worry” to describe the external pressures recent events have placed on the population. For those whose cup was already half-full before COVID, she says, it is now overflowing.

“All of us have quite a high level of stress as we cope with the changes around us, and for those already carrying those high levels of stress, or who are prone to feeling the impact of those difficulties more, we are seeing an increase in mental health difficulties,” she says.

“It’s okay to say to people, ‘Actually I’m tired, I’m not coping so well at the moment’, or ‘I’m finding these circumstances quite difficult’. We should feel okay with saying that, because acknowledging the difficulty of what we have been through – or are going through –is really important.”

Mental health triggers

Valerie Ling, a clinical psychologist who has done considerable work with staff and students at Moore College, and with clergy through the Centre for Ministry Development, says there isn’t one simple thing triggering mental health problems for people.

She separates it into three elements. First is the idea that, whatever is thrown at me, I can manage, and COVID has shown this is not a given. Second is the “other”, which, she explains, assumes that “even if bad stuff happens, people are generally good – but the toilet paper hoarding, people bashing others and racist comments shatters that”.

Third is the idea that, generally speaking, even if bad things happen, the world is a predictable and stable place. However, she says, “COVID smashed everything. Are we sick? Are we really sick? What if we’ve got no symptoms? How do we know? COVID’s just smashed all of those assumptions.

“What we know of other epidemics is that people go through different stages. In the first stage, everybody who hasn’t lost their job or come into acute distress because of COVID is just adjusting to life, so there’s a survival mentality that blocks out anything else.”

“…now we’re going out back into the world, people’s anxieties will increase.”

Mrs Ling says that after an epidemic there is an increase in depression symptoms as a result of the isolation, and an increase in anxiety symptoms due to people’s fear for their health.

“When we were in isolation that was easy because we could all stay home, but now we’re going out back into the world, people’s anxieties will increase.

“Then there’s the post-traumatic type reaction, which comes later – even up to a year afterwards for our health care workers, our teachers, and those who felt like they had to hold the fort during COVID-19… now we’re also entering the winter season, which typically is an aggravated time for mental health in general, so we’re already seeing our current clients not coping very well.

“Churches need to be very careful how fast they go back because people’s mental health is fragile – in that they worry about re-exposing their elderly parents, or people who they love, to infect them – and it will be staff on the ground who will feel responsible for these things.”

It’s not a faith issue

One of the least helpful things that can happen if someone says they are struggling with mental health issues is to dismiss them, expect the problem to go away or suggest that the person with the illness and/or their family are somehow lacking in faith.

“That’s a really important message,” Dr Condie says. “Mental health problems are not primarily spiritual problems… it’s an illness in medical terms that has an objective cause. Someone infected with Coronavirus or cancer, that’s not their fault, we don’t criticise them for that… and it’s the same with mental health.

“Rather than say this is due to lack of faith, [mental illness] needs treatment just the way a physical illness requires treatment.”

Mrs Wake agrees. In early May she took part in a webinar on faith and mental health with her church, St Paul’s, Castle Hill; this message was something she and the other two professional Christian women who led the event were keen to send to those who took part.

“We really didn’t want it to be shame-provoking and we didn’t want it to come across as trite – that these things are easy to do and ‘just love Jesus and everything will be okay’,” she says.

Sometimes that is the message that people hear… but we are works in progress, all of us, so we are going to struggle with things in this world and we each struggle in different ways.

“In doing the webinar we wanted to encourage people that it’s okay to be experiencing these difficulties, to normalise the fact that this is a tough time, it’s okay not to be okay and that lots of us are seeking help at the moment.”

“[mental illness] needs treatment just the way a physical illness requires treatment.”

How to respond

There are no easy, quick fixes here. Given the havoc COVID has caused in a range of health, social and economic areas, the country could be declared COVID-free tomorrow, but its knock-on effects aren’t simply going to disappear.

So, what do we do? First, if we (or someone we know) have a level of stress, anxiety or depression that’s impairing our day-to-day capacity to function, we need to seek medical help.

Says Dr Condie: “For some people the grief we’re experiencing right now, the losses that we’re experiencing and the stress that we’re under is going to create some symptoms. However, when that impairment comes into play, that’s when people do need to get checked out. Start off with your GP and, if necessary, they’ll refer you to a mental health professional. And yes, with those conditions you can’t just suddenly talk yourself out of it or pray yourself out of it.

“The message I want people in our churches to hear is that people struggling with mental health need our support, not our judgement. They’re already really good at beating themselves up about what’s going on with them – they don’t need anybody else to join that chorus! They need people to walk alongside them, to support them, to care for them. It’s what God does.”

In the webinar, Mrs Wake and her colleagues focused on people finding, in Christ, their security amid change, a satisfaction amid worry and significance in isolation.

“When we have that foundation… it helps us to face the difficulties that we’re coping with,” she says. “This is an experience that many people are having. Let’s talk about it and try to encourage each other to focus on the hope we have in Christ, but also focus on the everyday activities we can be doing to care for ourselves and each other.”

Dr Condie says the first thing people need to remember is that they are very complex beings with “profound” interconnections between mind, body and spirit.

“All influence each other,” he says. “Trying to take care of our bodies at a time like this is eminently wise. So, things like good sleep hygiene, nutritious diet, getting exercise: this is part of the way God has made us, and it’s foolishness to ignore who we are as human beings. There’s also a lot of evidence that paying attention to the spiritual aspects of who we are as human beings is profoundly significant for our wellbeing. Even secular research is saying this now.

“Here is a God who stands by our side. Those sorts of things can shape our mindset and lift some of those anxious feelings.”

“The wonder of Christian faith, as opposed to other forms of spirituality is that it’s grace-based, so my sense of worth is gifted to me by God… It’s removed from that whole performance mentality that drives our society. Here is a God who stands by our side. Those sorts of things can shape our mindset and lift some of those anxious feelings.

“Part of helping ourselves, and others, from a Christian perspective is not to think you can just read a few Bible verses and everything will be fine. It’s really much more complex… but God can bring good even out of our difficulties (Romans 5:3-5) and he does do that.

“That sort of biblical framework does really assist us… being reminded of these truths is not only good for our souls, it’s good for our mental health.”

Resources:

- Tackling Mental Illness Together by Alan Thomas

- Mentalhealthinstitute.org.au

Mental health symptoms

For children

Most children will feel anxiety in new and uncertain situations. However, they may need some extra support when:

◦ their anxiety seems disproportionate to the situation

◦ anxiety interferes with school and play

◦ they have significantly disrupted sleep/eating

◦ they exhibit increased irritability

◦ there is behavioural acting out

◦ they have significant distress being separated from caregivers

◦ there is regression – bedwetting, thumb sucking or nail biting in children who had previously moved on

For everyone

◦ Frequent panic attacks and/or pervasive low mood

◦ Increasing avoidance of feared situations

◦ Interruption in sleep and eating patterns

◦ Interference in daily living

◦ Significant impact on mood and functioning

◦ Problem-solving does not help

◦ Natural coping resources are overwhelmed

Source: Valerie Ling