There are many different reactions to the new situation of the Coronavirus pandemic. This is one of the more helpful ones.

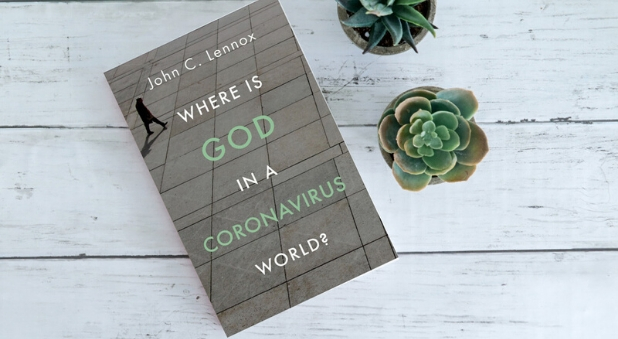

Taking only a week of writing, author and Professor of Mathematics at Oxford University, John Lennox, has dashed off a short book – which he describes as the kind of thing he would say if someone sitting in a coffee shop with him was to ask the question, “Where is God in a Coronavirus world?”

The result is a simple, easy-to-read defence of the Christian understanding of God in the face of what Lennox calls “a perplexing and unsettling time” when “most of our old certainties have gone”.

Lennox provides a straight forward treatment of the problem of evil

It is a book with evident strengths and weaknesses. Its strengths lie in Lennox’s straightforward and clear treatment of what turns out to be another version of the classic problem of evil. He frames the issue in terms of worldview – that is, “the framework, built up over the years, which contains the thinking and experience that each of us brings to bear on the big questions about life, death and the meaning of existence” (p. 22).

Atheism is quickly dismissed as failing because it ultimately posits a world not only without God, but without even good or evil as well. Lennox is sure that this is simply not liveable.

"A world without good and evil is not liveable"

Most of the book is taken up with the question of how there can be a Coronavirus if there is a loving God. Lennox begins by noting that viruses, like earthquakes it turns out, have an upside for human flourishing as well. He explains the reality of what he calls “deep flaws both in human nature and physical nature” (p.44).

Evidence for a God we can trust

Ultimately, however, debating the question of what a good, loving, all-powerful God should, could or might have done leads to no satisfactory outcome. Lennox would rather the reader look at the different and better question of whether, in the face of a universe both of biological beauty and deadly pathogens, there is any evidence of “a God whom we can trust with the implications, and with our lives and our futures” (p45).

The answer is found primarily in Jesus, whose resurrection is the guarantee of ultimate and welcome justice, and whose cross and resurrection offers “forgiveness and peace with God that can be known in this life and endures eternally”.

Finally, Lennox offers advice on how Christians should respond to the pandemic in a chapter that extensively quotes C.S. Lewis on living with atomic weapons, a recent article about Christian responses to other pandemics throughout the centuries, and the moving account of a sufferer of motor neurone disease, likening her struggle to the successful climb to the top of the mountain.

In so brief a book so hastily written the weaknesses of Where is God in a Coronavirus World? are also evident, if perhaps unavoidable. It gave me the impression of trying to cover far too much material far too quickly to be really satisfactory. Yet in the right circumstances this short publication could still be helpful in provoking a reader to further reflection and exploration of the important questions that it raises.

Bishop Robert Forsyth “retired” as Bishop of South Sydney in 2015. He is now an assistant minister at Church Hill Anglican.