As the music world farewells Michael Jackson, the king of pop, academia mourns the loss of a don of truly biblical proportions. Martin Hengel was Professor of New Testament and Early Judaism at Germany's prestigious University of Tübingen from 1972 until (as Professor Emeritus) his death last Thursday (July 2). The author of dozens of important monographs and literally hundreds of technical articles, Professor Hengel, originally a successful businessman, was the scholar's scholar, as comfortable in the classical sources of Greece and Rome as he was in the many and varied writings of Jewish and Christian antiquity.

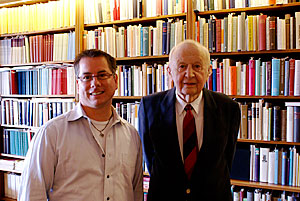

I had the enormous privilege of conducting what was perhaps Martin Hengel's last full-scale television interview. When the film crew and I met him in his flat overlooking the Neckar River in central Tübingen I was struck by several things. First, his enormous private library, described by his academic colleague Peter Stuhlmacher, whom we interviewed later that day, as "perhaps the finest private collection in Europe". Actually, his "flat' is two spacious interconnected two-three bedroom apartments, one for him and the warmly hospitable Frau Hengel and one for books"”at least four large rooms filled to overflowing with scholarly tomes written in German, English, French and Italian, as well as all of the relevant primary sources in Hebrew, Aramaic, Syriac, Coptic, Greek and Latin. During the interview I couldn't help gazing around the room and noticing the countless slips of paper peering out of so many of the items on the shelves. These books had been analysed and absorbed not just consulted and displayed. I left his home feeling slightly fraudulent as a New Testament scholar.

I had the enormous privilege of conducting what was perhaps Martin Hengel's last full-scale television interview. When the film crew and I met him in his flat overlooking the Neckar River in central Tübingen I was struck by several things. First, his enormous private library, described by his academic colleague Peter Stuhlmacher, whom we interviewed later that day, as "perhaps the finest private collection in Europe". Actually, his "flat' is two spacious interconnected two-three bedroom apartments, one for him and the warmly hospitable Frau Hengel and one for books"”at least four large rooms filled to overflowing with scholarly tomes written in German, English, French and Italian, as well as all of the relevant primary sources in Hebrew, Aramaic, Syriac, Coptic, Greek and Latin. During the interview I couldn't help gazing around the room and noticing the countless slips of paper peering out of so many of the items on the shelves. These books had been analysed and absorbed not just consulted and displayed. I left his home feeling slightly fraudulent as a New Testament scholar.

I was also deeply impressed by Hengel's humility. I interviewed a dozen experts in the making of the documentary, all of them leaders in their various fields. A few seemed rather aware of their importance. Others, notably Hengel, were as interested in each of us"”a junior scholar, cameraman, sound guy, director, producer"”as we were in them. As we enjoyed coffee and Brezel following the formalities, Herr and Frau Hengel peppered us with questions about our work, our families, life in Australia and the various other scholars we knew. It is a special kind of person who can have so much to give and yet prefers to ask questions.

Let me say something about Professor Hengel's huge scholarly contribution (which, curiously, is greater in the English-speaking world than in Germany). As I wandered around his library I came across a section containing his own authored and edited volumes, about 80 in all. I was reminded not only of how prolific he was but also how very significant. Few scholars can expect to write something others will describe as "landmark'. Hengel is a one-man landscape. At a time when faddish scholars were downplaying the connections between Jesus and Judaism and playing up the connections between Christianity and ancient pagan religion, Hengel was busy clarifying our picture of first-century Palestine and then trying to set Jesus and the Gospels within that secure context. He wrote a still-standard text on the rise of Jewish revolutionaries in the period (known as the Zealots). In his Judaism and Hellenism he carefully described the relationship between ancient Jews and the surrounding Greek culture. The significance of this last work cannot be overstated. It is now historically impossible to speak of a neat distinction between Greek and Jewish cultures in antiquity, and the once-common suggestion that our Greek Gospels could only contain a distant echo of an Aramaic-speaking Palestinian Jew is now historically untenable. The prominence of the Greek language among Jews even in Jerusalem makes it virtually certain that Jesus' teachings were being retold in Greek immediately after his death, if not during his own lifetime.

Hengel also wrote works directly on Jesus. In The Charismatic Leader and his Followers, he refuted the suggestion of theologians like Rudolf Bultmann that the early church's proclamation of "the Christ' had little to do with the historical ministry of Jesus of Nazareth (one still occasionally hears this sort of thing from popular writers like Bishop John Shelby Spong). In The Son of God, he challenged the notion that Christian beliefs about a "divine son' derived from pagan myths. He showed instead that the New Testament descriptions of Jesus derived from Jewish traditions (not pagan ones) current in Jerusalem in the period of Jesus himself. Much more could be said about Hengel's academic contribution. For instance, his work on the apostle Paul, the man occasionally credited either with inventing or perverting Christianity, was equally significant. "Where other specialists had thought the Acts of the Apostles and Paul's letters too remote for trustworthy historical contact with Jesus," says Professor Edwin Judge, one of Australia's foremost classicists and experts on Roman history, "Martin Hengel has decisively tightened the connection between Jesus and Paul." On hearing of Hengel's death, Professor Judge praised the German scholar for his "stream of realistic studies of Jesus and his followers, towards the comprehensive history of early Christianity."

One final reflection on the man I describe in the documentary as "after Bono " one of my greatest heroes". During my brief tour of his library, I came across an important book by a well known Cambridge don who was seriously ill at the time. I remarked, "I love this book, Herr Professor". "Ah," Hengel replied, "dear Graham is most unwell. I must remember to keep praying for him." I was taken aback. None of the scholars I had interviewed up to that point"”some of whom were Jews, some Christians (of various shades)"”had mentioned anything "spiritual'. It was a strictly historical documentary, after all. Yet, here was Martin Hengel, easily the most prolific and revered scholar among my interviewees, seamlessly moving from quotations of second-century Greek texts (in the original language and from memory) to talking about his heartfelt prayers for a fellow scholar. Make no mistake. Hengel was no evangelical theologian"”he wasn't a theologian in the proper sense at all. He was a critical historian of Jewish and Christian antiquity and, frankly, some of his views on the Bible make evangelicals wince. But he was also a man of deep piety. His enormous learning was never something in conflict with his core conviction about Jesus, namely, that this carpenter from Nazareth truly is the risen Son of God who stands ready to hear our prayers and grant us His grace. Into this reality Professor Martin Hengel has now fully entered.

John Dickson’s half-hour interview with Martin Hengel can be viewed at The Centre for Public Christianity’s web site