What is an Anglican? How is Anglicanism being stretched out of shape to be unrecognisable? Sydney’s Doctrine Commission has produced a report on authentic Anglicanism and the following is an abridged version, with some language simplified for general reading. See the full report at bit.ly/authenticanglicanism

“Anglicanism” is the label attached to a form of Christian corporate life that traces its theological convictions and ecclesiastical practice to the New Testament, with an especially formative period during the English Reformation. Its congregations are part of the ‘one holy catholic and apostolic church’ confessed in the ecumenical creeds, yet they share distinctives that mark them out from other communions and denominations.

These distinctives could be defined and described in a number of ways, of which two are most common: a phenomenological approach (which emphases description) and a theological approach.

A phenomenological approach often begins by drawing attention to the diversity of practice that has emerged over the past 500 years, despite numerous Acts of Uniformity. It then proceeds to infer from this a distinctive “ethos” of Anglicanism.

The advantage of this approach lies in its attention to history and the way Canon law has or has not shaped the practices of the church. Its disadvantage lies in the way it sidesteps the question of what Anglican identity should be on the basis of its foundational documents. In other words, it ignores what is normative.

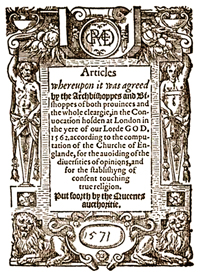

A theological approach, in contrast, draws attention to the common convictions that shape the doctrine and practice of Anglican churches, which have proven to be stable markers of Anglican identity. These arise from Scripture and are given formal expression in the Articles of Religion (1571), The Book of Common Prayer (1662) and the Ordinal (1662), together known as “the formularies”. The theology contained in these documents provides a summary of an Anglican reading of Scripture and its application to Christian corporate life.

Anglican practice ought to be explained by Anglican doctrine ...

The advantage of this approach is the way it gives due weight to these foundational documents of Anglicanism and the intention of those who wrote them as part of their attempt to reform England. Its disadvantage lies in its potential to be doctrinaire and to disregard the historical complexities of application.

This report will take a theological approach, convinced that it has always been the case that Anglican practice ought to be explained by Anglican doctrine. Put differently, the confessional aspects of Anglicanism are (or at least should be) the best explanation of its practice and the way it orders ministry.

In order to avoid the disadvantages mentioned above, and to prevent a presentation of Anglicanism that is merely a projection of our own preferences, this theological approach is anchored in the formularies, recognising that the formularies themselves allow for a flexibility to respond to the changing context of the church in its ministry and mission.

Whatever its accidental features may be, the Anglican Church can be authentic only on the basis of its confessions of faith as they are expressed in the formularies. Perhaps the three most distinctive elements of authentic Anglicanism are its confessional, liturgical and episcopal character. However, before turning to these, it will be important to consider the place of Scripture in authentic Anglicanism.

The place of Scripture

Every legitimate form of church gives a central role to engagement with the canonical Scriptures of the Old and New testaments. The reading and exposition of Scripture has been part of Christian gatherings since the time of the apostles.

However, the English Reformers recognised a critical role for sustained engagement with the Scriptures as a key strategy for the reformation of the English realm. Archbishop Cranmer, the chief architect of Reformation Anglicanism, presented this as a return to “the godly and decent order of the ancient Fathers”.

Cranmer was convinced that the word of God written (Article 20 of the Articles of Religion) is powerful and that the Spirit is able to transform lives as he writes God’s word on human hearts. Only doctrine that can be proved by Scripture is to be believed as “an article of the Faith” (Articles 6, 20).

Nevertheless, Cranmer did not restrict those things done within church to only those things that could be proved by Scripture. Rather, he retained “ceremonies” from the pre-Reformation because they promoted decent order in the Church, as they pertain to edification. In other words, from the beginning Anglicans upheld the normative principle – what is not forbidden in Scripture is permitted – rather than the regulative principle that only what is commanded in Scripture is permitted.

In line with this new and somewhat distinctive emphasis on Scripture as the means of national reform, access to the Bible in the vernacular was championed. When The Book of Common Prayer was presented, its shape was determined by and its language saturated with the words of Scripture. This even found expression in Elizabethan church architecture, which placed neither an altar nor a pulpit in the most prominent place, but rather the Bible on a lectern.

Confessional character

To speak of Anglican identity as “confessional” is not merely to make a statement about its contingent historical foundations. It is to align that identity with a set of normative doctrinal commitments. The content and structure of the Articles of Religion give formal expression to these.

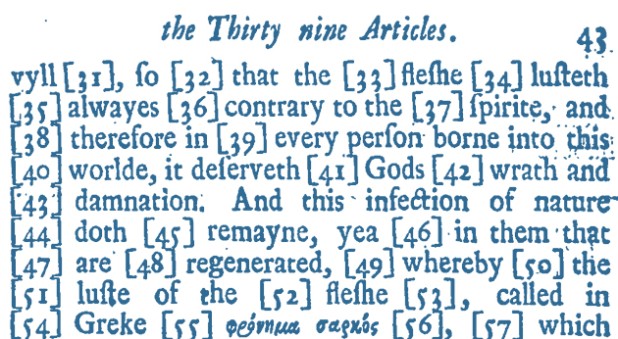

First, the articles uphold the supreme authority of Holy Scripture as “the pure Word of God” and the norm of Anglican identity (Article 6). The unique and irreplaceable foundation of Scripture ensures that all doctrinal statements made by the church, including the articles themselves, are derivative and subordinate in character (Article 8). Their validity and normative force only arise from their consistency with the totality of biblical teaching (Articles 20, 21). Besides attesting to the final rule of Scripture, the articles provide an authoritative doctrinal framework that makes clear the way Anglicans read Scripture – not least in their insistence that no part of Scripture is to be read in a way that contradicts another (Article 20). In this the Anglican approach to Scripture finds its origin in, and shares much in common with, other early confessional documents of the European Reformation, both Lutheran and Reformed.

In addition to their commitment to the supreme authority of Scripture, the Protestant character of the articles is evident in their affirmation of the doctrinal authority of the ancient creeds (Articles 1-5, 8), the depraved condition of humanity, sovereign election to salvation in Christ, the necessity of justification by faith in the finished work of Christ alone (Articles 9, 10, 11, 13, 17, 18, 31), the two dominical sacraments of “Baptism and the Supper of the Lord” – especially the baptism of children (Articles 25-28).

It is made even more clear by the rejection of key elements of distinctively Roman Catholic piety and doctrine. Consequently, any interpretation of the articles that contradicts their essentially Reformed character is a clear violation of their historical intention. It is undeniably true the articles have been received and interpreted by Anglicans in ways that do not neatly align with their Reformed heritage. It is also true their original historical setting does not neatly align with the global context of Anglican identity today. Contextualising these doctrinal commitments in a way that is sensitive to the breadth of cultures represented is a pressing need (e.g., concerning the character and expression of the church’s establishment in relation to the state). However, respecting and preserving their enduring Reformed character remains paramount.

Liturgical disposition

The first major formulary of the English Reformation was The Book of Common Prayer (BCP). Authorised and issued in 1549, it replaced various pre-Reformational service books. It was written in English, and the Reformation principles of justification only by faith and the sufficiency of the Scriptures for salvation significantly shaped the services.

The 1662 version of The Book of Common Prayer has had a global influence and is still regarded in many places, including in the Constitution of the Anglican Church of Australia, as “the authorised standard of worship”.

The major principles that shaped the “Publick Liturgy” of the BCP were explicitly outlined in its prefaces. These were:

- preservation of the best liturgical practice of the previous 15 centuries;

- a simplification of the many books and devices needed to conduct public worship;

- purification through the removal of unbiblical aspects of Roman Catholicism;

- intelligibility of the service through using understandable language that enabled participation and edification; and

- uniformity of worship across the thousands of parishes in order to strengthen unity between parishioners and throughout the national church.

While the BCP is no longer used in many contemporary churches, its doctrine and principles continue to significantly shape authentic Anglican corporate worship. What we do when we are gathered by the Spirit to hear God’s word, to respond to that word in prayer and praise, and “to stir up one another love and good works” does need to be expressed in an appropriate contemporary idiom. Cranmer envisaged that revision to the BCP would continue, guided by the principles mentioned above. Most importantly, an authentically Anglican approach to liturgy is undergirded by an important scriptural interconnectedness in form and substance.

Episcopal government

Finally, a confessionally Anglican identity is distinctively episcopal, with a commitment to the threefold order of Christian ministry: bishops, priests (presbyters) and deacons (Article 36). This is reflected in the BCP and affirmed in the Ordinal, the third traditional formulary of Anglicanism. It is also embedded in Section 3 of the Constitution of the Anglican Church of Australia.

Why did the English Reformers retain this threefold order when others on the Continent dispensed with it? The answer lies in the Reformation principles already identified in the preface to the BCP. One of these sought only to abolish ceremonies that were a perversion of Christianity and retain other traditional aspects of church experience. Retaining forms and practices that were not inimical to the gospel reinforced the conviction of the Reformers that they were not creating a new church but calling a compromised church back to its true heritage. The emergence of Anglicanism was an exercise in reformation, not reconstruction.

Cranmer believed episcopacy ought to be retained as it was compatible with the teaching of the Bible and had been a consistent feature of ecclesiastical order “from the Apostles’ time”. Yet he did not believe bishops are essential to constitute the church – rather, they are provided for its welfare.

The consecration service constructed by Cranmer emphasises the upholding and teaching of Holy Scriptures as central to episcopal ministry. This emphasis on the role of an Anglican bishop as a guardian of the faith is significant in grounding the spiritual authority associated with the role of bishop. It is an authority derived from the authority of God’s word and its legitimacy is forfeited when the bishop begins to teach or condone things contrary to the Bible.

Anglican “identities”

This report has endeavoured to give a theological account of authentic Anglicanism that is grounded in its foundational documents – The Book of Common Prayer, the Ordinal, and the Articles of Religion – because of a fundamental conviction that doctrine should determine practice rather than the reverse. What we are committed to believe as Anglicans is given to us in the formularies, and those beliefs fleshed out in practice lie at the heart of what it means to be Anglican.

However, through the centuries other Anglican “identities” have been fabricated that are grounded quite differently. Some have attempted to characterise Anglicanism as a middle way between Catholicism and Protestantism. However, this suggestion has fatal flaws. Firstly, the term is not explicitly used by the first English Reformers. It finds no expression in the Articles of Religion, which repudiates Roman doctrine and that of the Anabaptists while affirming mainstream Reformed doctrines, as noted above. The idea of a “middle way” does not appear even in the works of Richard Hooker (a 16th-century Anglican theologian), to whom it is regularly attributed but, rather, in the context of the high-church Oxford Movement of the 19th century as part of a call for a more “Catholic” form of Anglicanism.

“it has served as an open invitation to intellectual laziness and self-deception” and “has led to an ultimately illusory self-projection as a Church without any specific doctrinal or confessional position”

Bishop Stephen Sykes

From at least the time of the 1930 Lambeth Conference, it has been common to speak of a defining characteristic of Anglicanism as “communion with the See of Canterbury”. The expression had been in use for a century by that time, but it was not until the second half of the 20th century that it was elevated to the measure of membership of the Anglican communion, and so of Anglican identity. To define being Anglican by communion with the See of Canterbury also raises a number of very difficult questions, such as what to do when the See of Canterbury is occupied by someone who has abandoned the teaching of Scripture at one point or another.

A third approach to defining Anglicanism, adopted by some in recent years, has been to emphasise toleration of doctrinal diversity as characteristic of Anglicanism. This view was promoted strongly by Anglican theologian F. D. Maurice in the 19th century and Archbishops Runcie and Carey in the 20th. Perhaps none has been more scathing of this conception than Professor (later Bishop) Stephen Sykes, who wrote of how “it has served as an open invitation to intellectual laziness and self-deception” and “has led to an ultimately illusory self-projection as a Church without any specific doctrinal or confessional position” (The Integrity of Anglicanism, 19).

None of these alternatives are satisfactory as a definition of authentic Anglicanism, even if they provide descriptions of perspectives valued by many contemporary Anglicans. Anglicanism that is true to its heritage is not indifferent when it comes to theology. It has a clearly confessional character that is not simply a matter of doctrinal assent but also determines church practice and even the shape of church government: confessional, liturgical and episcopal.

The Rev Dr Mark Thompson is chairman of the Sydney Anglican Doctrine Commission.