If you close your eyes and inhale the sea air and feel the warm summer sun on your cheek you might just find it possible to believe that a fair go still exists in Australia. We have low unemployment and a high standard of living, a solid social security safety net and plenty of casual work opportunities for those who look for it. Don't we?

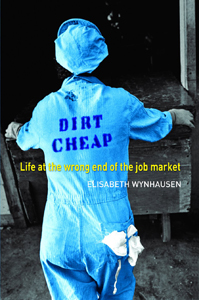

Journalist Elisabeth Wynhausen decided to find out for herself what life is like on the minimum wage. The result is Dirt Cheap: Life at the wrong end of the job market. The statistics say that an increasing proportion of employment in Australia is on a casual basis. But what is the human side of the story? Taking her cue from George Orwell, who seventy years ago recorded his experiences of poverty and homelessness in Down and Out in Paris and London, Wynhausen's project is to take leave without pay for nine months and to try and find work without the aid of her impressive CV and qualifications as a 55-year-old woman. She works for short periods as a kitchen hand, an office cleaner, a factory worker, a checkout chick and in the laundry of a nursing home.

Wynhausen depicts with delightful sympathy some of her fellow workers - especially Svetlana, the Russian immigrant who obsessively cleans her hotel kitchen. Work - even the most menial and underpaid - has the capacity to bestow real dignity on people. However, Wynhausen's point is that this dignity is being eroded by the conditions of employment in Howard's Australia. Take Wynhausen's job at "the Store" (which she doesn't identify but must be a branch of a US-owned chain with "mart" in the name): her hours are so irregular that there is no chance of a social bond with her fellow workers; she is inadequately trained so that mistakes are humiliatingly frequent; she is kept in fear of the supervisors who have the power to reduce her hours to virtually nothing; she is expected to work unpaid overtime; and the staff levels have been cut such that those who do work at the store do so under conditions of extreme stress. Whatever dignity this work might have is stripped away, leaving the workers demoralized. In several of the jobs, too, there is extreme physical pressure.

Neither does Wynhausen find work easy to obtain in the first place. She is made to nag and to beg prospective employers for mere crumbs of work. She finds government agencies next to no help in locating work. On the wages that she earns she is barely able to afford the rent. Spending money on "luxuries" - like a fast-food meal - is out of the question. At every point necessities like public transport and work clothes eat into her meagre earnings.

Perhaps the most alarming thing about her experience is the way she is treated. Wynhausen finds that being a casual worker in a menial job makes you virtually invisible. She is treated with rudeness and coldness by those she serves: very rarely with any human warmth. It is as if she has slipped into a fog that makes others blind to her. The under-appreciation was perhaps the most soul-destroying thing of all.

I don't know what the worst job you ever had was. I once delivered advertising leaflets to letter boxes at the rate of 2 ½ cents a page, which meant I could earn about $75 if I walked hard for 8 hours straight.

It wasn't so bad: I was just earning some pocket money while I was at uni and was happy for the exercise. But if the statistics are to be believed, more and more Australians are trying to earn a living doing these casually-employed "menial" jobs. The credibility of the Union movement is in tatters; and with the Howard government promising further reforms to make the hiring and firing of casual workers easier, the future for such workers looks increasingly bleak.

Wynhausen's book is a timely challenge to our nation; but it is also a challenge to Christians and the churches. Who will speak for the emerging underclass of workers now that Unions have become so docile? How do we treat those who work around us and under us in the so-called "menial" jobs? Do we know them, or are they invisible to us? Are we even now participating in and advancing this structural imbalance in our economic system in our businesses? Are our employees in nursing homes and camp-sites and so on treated better than they are in other places of work?

Upcoming legislation will only strengthen the hand of employers against these workers. If Christians are really interested in "family values", we would do well to lobby the government to ensure that it is possible for people on the lowest wages to at least take their kids to Sunday School and to spend time with them. The business sector needs to be restrained in its unbridled pursuit of profit because an inequitable system will put immense pressure on marriages and on parents. We need to see this not as a Liberal vs Labor issue, but as a matter of listening to the Word of God.