King of Kings remains the bench-mark in many respects for large-scale retellings of the life of Jesus. It clearly demonstrates everything that can go right and wrong with visual reproduction of the Gospel story.

Narrated by Orson Wells and directed by Nicholas Ray, this 1961 successor to the original 1927 Cecil B. DeMille production succeeds on every cinematic level. A prodigious budget allowed for excellent scale in the construction of elements of Jerusalem, its Temple, the palace of Herod and the villages of Galilee on site in Spain. The storyline also expands outside the strict confines of the Gospel narratives, beginning with a historical background of the persecution of the Jews with the arrival of the Romans in Palestine. It is on to this detailed backdrop that Jeffrey Hunter's Jesus walks.

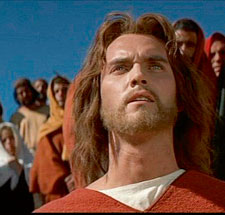

Kings of Kings bears all the hall-marks of a 1960's American studio production. The Middle East is populated with beautiful, pale-skinned American actors and actresses. Hunter himself is the original blonde-haired, blue-eyed Jesus. Even the costume of the woman caught in adultery looks like it would be more at home on a Las Vegas stage than the Palestinian hinterland. However, for all its anachronisms, the production is strangely timeless.

Kings of Kings bears all the hall-marks of a 1960's American studio production. The Middle East is populated with beautiful, pale-skinned American actors and actresses. Hunter himself is the original blonde-haired, blue-eyed Jesus. Even the costume of the woman caught in adultery looks like it would be more at home on a Las Vegas stage than the Palestinian hinterland. However, for all its anachronisms, the production is strangely timeless.

The writing in King of Kings is first-rate, the acting superb and the music iconic. Ray's directing is both creative and emotive, particularly in the way he portrays Jesus' effect on a scene without having to show him physically. In fact it is a clear visual theme, and one of the positives for the production, that no-one can interact with the Son of Man without coming away fundamentally changed.

The script includes extensive quotations from the Bible, however this is where the film's faults really begin to emerge. The passages are mixed together with a range of fictional accounts, but all delivered in the same archaic 'voice of history' so that they emerge with equal authority. Elements like the three wise men owe their inclusion to tradition; others, like Jesus' visiting John the Baptist in jail, and Pilate's wife appearing at the Sermon on the Mount, are included for dramatic purposes. However there are a range of other scenes that are included to promote philosophies that sadly run counter to the Christ of the Gospels.

To begin with, King of Kings is a particularly Roman Catholic production. It includes additional scenes showing Mary meeting with John the Baptist, encouraging the woman caught in adultery, promoting Jesus' message and showing prescience of his coming sacrifice. Jesus is also shown in white clothes with a red surplus that strongly resembles the formal garb of the Pope, and often uses his hands in a way that suggests benediction.

Potentially the worst elements, though, are those that shift Jesus words away from a call to repentance and direct it towards a message of works-based righteousness. "The Kingdom of God," Hunter's Jesus says, "is within you." And it is a kingdom that will have nothing to do with overthrowing the Romans - not because it has its eyes on Heaven, but because conquering is wrong, "And to conquer them would make you no different than they." In his mouth the Sermon on the Mount becomes a call to a superior standard of morality, rather than a demonstration of just how far we have fallen from God's requirements. "Treat your fellow man as you would have him treat you," has become the whole law of the Prophets. Giving God precedence over everything has fallen by the wayside.

King of Kings is the best of the 'unearthly' Jesus films, those that portray Jesus as set apart and different in character and motivation from the rest of us. But as a consequence his humanity is wanting and it is hard to consider him being tempted by anything but the most cerebral sins. It is a fantastic example of how the elements of cinema can be combined to create a story tharemains remains powerful and convicting. The tragedy is that when script devices rule over a story, truth is the first casualty. In Kings of Kings Jesus' death is the tragic loss of a man too good for the brutal time in which he lived. His eventual resurrection appears more spiritual than physical, which is appropriate considering he ultimately symbolizes what corrupt flesh can aspire to be - the ascended man.