One criticism levelled at modern literature is the absence of a compelling story. The allegation is that style has been elevated in importance while the purpose of the novel " to tell a story " has been downplayed to the point where an interesting plot is an optional extra.

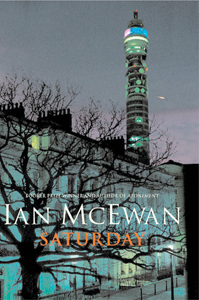

Multi-award winning British novelist Ian McEwan regularly disproves such arguments. McEwan marries beautiful writing to enthralling stories. His latest is the post-9/11 novel, Saturday.

Set over the course of a single day, Saturday begins in the early morning of February 15, 2003 as a sleepless neurosurgeon, Dr Henry Perowne, gazes out his bedroom window. From his secure vantage point he sees a plane whose fuselage appears to be alight.

This day should follow the pattern of his normal Saturdays; squash with a colleague, a visit to his mother, shopping for dinner. Yet from the outset something is amiss. The burning plane reminds him of 9/11.

Perowne's life exudes contentment and privilege. He is happily married to Rosalind, a successful lawyer. Together with his wife, Perowne dotes on their two adult children. Such domestic tranquillity is unusual in fiction. The conflict, necessary to fuel a novel, must come from outside.

It comes in two forms; the tension of the post-9/11 world and a dangerous, unhinged individual whom Perowne chances to meet. On the way to his squash game, as the doctor ponders the threat of unknown zealots destroying his life, a red BMW pulls out and destroys his side mirror.

The incident angers him but his indignation at the damage pales when confronted with Baxter and his henchmen. They are a menacing trio with extortion in mind. Despite the possibility of a thrashing, Perowne is more concerned about the ringleader, Baxter, than his own safety. The younger man's aggression cannot hide that there is something seriously wrong with him; the neurosurgeon believes it to be Huntington's Disease.

Escaping the incident with a bruised sternum, Perowne finds his mood utterly altered. He suspects that this encounter with Baxter will not be the last.

As danger invades Perowne's cloistered existence he begins to question the purpose of life. His musings leave little room for the divine " surely a global suffering denies the existence of a loving God, he reasons. But he does question his responsibility to humanity, to those beyond his immediate circle.

Despite Perowne's disdain for Christians, Saturday is imbued with spiritual notions. The key idea plays out like a parable. Christ commands us to love our enemies and pray for those who persecute us. It is this concept of reaching out to those who do us harm which the novel is based.

Subtle and at times gripping, Saturday is a beguiling read.