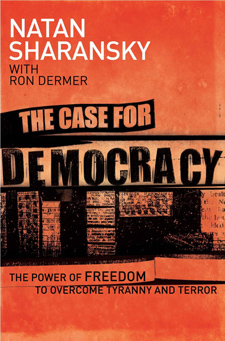

Natan Sharansky wants to see tyranny go the way of slavery, and he believes he has an approach that will achieve just that. But does his analysis of the road to a democratic and peaceful world wrestle with all the dimensions of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict that he is so involved in himself?

Sharansky was a Soviet dissident, jailed for nine years until in 1986 he became the first political prisoner released by Mikhail Gorbachev. He emigrated to Israel and in time sought and won political office. He served as a minister in coalition governments led by Benjamin Netanyahu, Ehud Barak and Ariel Sharon. He has been listened to by Presidents Reagan, Clinton and Bush. In this book he speaks personally and passionately from his long and, at times, direct involvement in the politics of the Cold War and the Middle East.

His basic conviction is that "the road to peace is paved with freedom' (263), and that fear societies, where dissent is repressed, and where dictators trample on human rights, will always pose a threat to lasting peace among nations. He argues that this is because tyrants will perennially seek to consolidate their hold over their citizens by inculcating in them fear of and competition against some external enemy. Tyrants do not have the incentives that democratic leaders, who depend on their people, have to avoid war. In Sharansky's view the best indicator of a government's true regard of its neighbours is seen in its regard of its own citizens. No matter what region you consider, a stable dictatorship is never, in the long run, better for peace than a democracy.

He also believes that fear societies are more vulnerable than they may seem. He argues that free societies (the democratic world) can overturn fear societies by confronting them and refusing to co-operate with them unless they begin to respect the rights and freedoms that God gives to all people. This is because all people desire freedom and would, if they thought it were truly possible, embrace a democratic form of government. This hope and desire for freedom is what dictators must constantly suppress in their citizens.

Sharansky argues that if powerful democracies like the USA consistently and uncompromisingly linked their support for non-democratic governments with proper compliance to internal reforms on human rights issues, then dissent would find a foothold in the society and in surprisingly little time the tyrant would be unable to continue to control his citizens. Sharansky believes that this dynamic applies to any non-democratic regime and that in this way freedom is powerful to send tyranny the way of slavery.

Sharansky gives an engaging account of how he saw this dynamic at work in the fall of the Soviet Union. He then gives a commentary on the Israeli-Palestinian troubles from the 1993 signing of the Oslo Accords to the present. As he sees it, the moral clarity amongst some US leaders (notably Reagan and Senator Henry Jackson) that led to the collapse of the Soviet fear society is sadly lacking when it comes to the Middle East. Sharansky names Arafat as a tyrant who should have been confronted. He believes the democratic world needs to recognise the fundamental and decisive difference between the free Israeli society and the Palestinian fear society, and stop condemning Israel and start confronting Palestinian tyranny.

Now I do not claim to know the shrewdest questions to ask, but one question is whether Sharansky has grasped the essence of why the Soviet Union fell and whether the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is amenable to the same kind of resolution.

Sharansky says yes, but I wonder whether Sharansky's analysis of the Israeli-Palestine conflict deals deeply enough with the issues of justice and of religious conviction that, it seems to me, complicate that conflict. On Sharansky's own account, the Soviets had to manufacture external enemies, to manipulate their citizenry into believing that a life or death struggle was occurring between the USSR and the West. In the end the people under the Soviets did not really believe this " their heart was not in it " and so this "conflict' evaporated when the political leadership fell.

Now is this the case amongst Palestinians? Perhaps not. Yasser Arafat may have relentlessly whipped up resentment against Israel, but did he start the fire? It seems to me that a deep perception of the injustice of their treatment by Israel, and a deep desire, not for prosperity and freedom per se, but for a right state of affairs in the world, fuel the fires of the conflict. Further, for many, that right state of affairs is properly described by Islam, and that spiritual root is, I suspect, deeper and more potent than the spiritual root of Marxism. It is certainly older and is proving vigorous across the globe today.

Communism, being atheistic, could not as effectively demonise capitalism on a religious level, and thus tap effectively into that powerful righteous anger (to give righteous a fully religious weight) which will induce people to utterly disregard their own (earthly) advantage. Yet both these elements, (it seems to this novice observer) seem to be present in the Palestinian-Israeli conflict.

I am loathe to pronounce Sharansky misguided in his approach to Palestine and Israel, given my own scant knowledge of the topic, but his lack of engagement with the issues of justice and religious conviction and their part in the conflict seemed to make his case less nuanced and persuasive.