When popular surveys were conducted for the best book of the last millennium and of the last century The Lord of the Rings was at the top much to the dismay of many a literary critic. It was indicative of the popularity of the fantasy genre of which Tolkien is a founding father and perhaps also of the movies that had captured the popular imagination.

Tolkien as many will know was a respected academic at Oxford holding a chair in Anglo-Saxon. The essay "On Fairy-stories" is the edited text of the 1938/1939 Lang Lecture delivered at St Andrews University. The Hobbit had recently been published and The Lord of the Rings was twenty years off being completed. This essay brings together Tolkien the academic and Tolkien the fantasy writer as he reflects on the purpose, limits and nature of fairy-stories. If Tolkien had not gone onto become a founding father of the fantasy genre this essay would never have seen the light of day. That is not to say the essay is not worthwhile but that you cannot help but think of the world of Middle Earth that Tolkien sub-created (to use his terminology) as you read it.

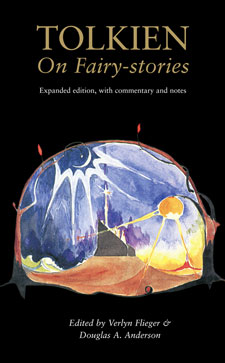

Having read Tolkien's essay "On Fairy-Stories" many years ago I thought when picking the book titled On Fairy-Stories that it would be a slim read. This however is the definitive edition of this essay including extensive notes, commentary, contemporary media reports and a history of the essay which all run to some 320 pages. Unless you have a particularly academic interest in Tolkien I would not bother reading the "manuscript versions" A and B of the essay though they do provide an insight into his creative processes. Similarly the extensive notes are not necessary if you are familiar with the genre of the fairy tale. I am sure Tolkien, who would have been familiar with textual criticism from his academic work, would be bemused to see his essay treated as some form of "sacred text".

Having read Tolkien's essay "On Fairy-Stories" many years ago I thought when picking the book titled On Fairy-Stories that it would be a slim read. This however is the definitive edition of this essay including extensive notes, commentary, contemporary media reports and a history of the essay which all run to some 320 pages. Unless you have a particularly academic interest in Tolkien I would not bother reading the "manuscript versions" A and B of the essay though they do provide an insight into his creative processes. Similarly the extensive notes are not necessary if you are familiar with the genre of the fairy tale. I am sure Tolkien, who would have been familiar with textual criticism from his academic work, would be bemused to see his essay treated as some form of "sacred text".

Counter-intuitively to what many would think for Tolkien the fairy story is about truth because it will at its best create a world which embodies truth and which has the "inner consistency of reality". While accessible to children they are not for children. For Tolkien his taste for fairy stories was "wakened by philology" and "quickened to full life by war" (p56). Fantasy is for Tolkien "story making in its primary and most potent mode" (p61) as it sub-creates a whole world which you can enter.

From a Christian perspective the Epilogue is the most intriguing part of the essay because he takes two of the distinctives of fairy tales " joy and truth and brings this analysis to bear on the story of the Gospels. He writes "the Gospels contain a fairy-story, or a story of a larger kind which embraces all the essence of fairy-stories. They contain many marvels " peculiarly artistic, beautiful and moving: "mythical' in their perfect, self-contained significance; among the other marvels is the greatest and most complete conceivable eucatastrophe. But this story has entered History and the primary world; the desire and aspiration of sub-creation has been raised to the fulfilment of Creation. The Birth of Christ is the eucatastrophe of Man's history. The Resurrection is the eucatastrophe of the story of the Incarnation. This story begins and ends in joy. " There is no tale ever told that men would rather find was true, and none which so many sceptical men have accepted as true on its own merits. For the Art of it has the supremely convincing tone of Primary Act, that is, of Creation. To reject it leads either to sadness or to wrath (p78) [eucatastrophe was a compound word created by Tolkien to mean good catastrophe].

For those who attended or listened to Professor Trevor Hart (from the same St Andrews University at which Tolkien's lecture was delivered) deliver the New College lectures this year on the topic "God and the Artist - human creativity in theological perspective" this book is a good follow up to Professor Hart's lectures which dealt briefly with the themes and history of this essay.

After the experience of the much publicised release of The Children of Hurin last year which was little more than a re-write of part of the volume of Unfinished Tales (published in 1980) I cannot help but think that there will be further attempts to republish "Tolkien" works in a way which will lead people to believe they are somehow new or re-discovered. As far as attempts go it is a much more useful one than The Children of Hurin. For those looking for more fantasy stories from Tolkien's pen this is not the book for you. It is rather for those who are interested in knowing what Tolkien thought was at the heart of a good fairy tale.