A new book highlighting a historical Sydney clergyman has also shown the close links of theological and scientific thought in colonial Australia.

This Wonderfully Strange Country by retired professor, geomorphologist and Anglican lay reader Dr Robert Young, documents the life of the Rev W.B. Clarke and his contributions to the burgeoning colony in Australia during the 19th century.

“I’ve always had a strong interest in how geology and other natural sciences developed,” Dr Young says. “Clarke in particular always struck me as a major feature in understanding the history of Australian science. Of course, it was all done in his spare time, as he was also the rector of St Thomas’, North Sydney over that period.

“The thing about Clarke is he covered such an enormous amount of material. He is known as the father of Australian geology, he was almost certainly the discoverer of gold and was also one of the first to conceive of the idea of former supercontinent, Gondwana. But quite apart from the geology he supported explorers – the likes of Leichhardt and Kennedy – and was a figure in the media as a journalist as well, particular through his work in and for The Sydney Morning Herald. He was quite remarkable.”

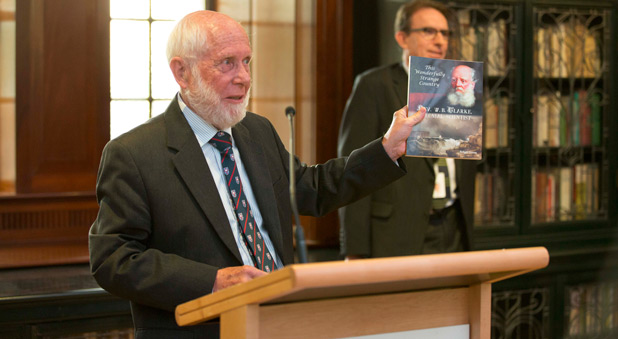

Last month’s launch of the book, which was hosted by the State Library of NSW, was attended by Anglicans, scientific society members, university professors and direct descendants of Clarke himself. The Bishop of South Sydney, the Rt Rev Robert Forsyth, spoke at the event, along with Dr Young.

One of the features of Clarke’s life, apart from his extensive scientific contributions, was his interest in social development. He spoke in favour of government-supported education and the primacy of teacher training, and was also very concerned with the status of Aboriginal people in the colony.

“He was very much a social critic,” Dr Young says. “He was very much concerned about what was happening and could happen to the Aboriginal population and, throughout his work, particularly his roles in the media, he was looking to see how Australia could develop itself into a more humane nation.”

The wide-ranging and exhaustive nature of Clarke’s work had its own impact on his family, with his wife and three children returning to England for 12 years because of homesickness. Clarke supported his family with his income from the colony until they returned.

What drew everything together for Clarke, Dr Young says, was his Christian commitment.

“It was in no way limited by science,” he says. “[Clarke] saw nature – a term he hardly ever used himself – as having no barriers and that allowed him to pursue everything.

“The theme that crops up over and over again in all his roles was a commitment to truth… whether in doctrine, in social investigation, in journalism, in geology or whatever, it was a commitment to the truth. That link between his Christian commitment and science is an answer I feel to anyone who feels there is a conflict there, from Huxley and Darwin – who he spoke to at the time – all the way through to Dawkins. For Clarke that just didn’t occur, and that makes him still relevant today.”

Feature photo: Dr Robert Young speaks at the book launching (credit - Merinda Campbell, State Library of NSW)