Socrates was famously executed in Athens for "corrupting the youth" of the city. In 1989, when I was in my first year of Arts at Sydney University I was ripe for corruption. So I signed up for Philosophy 1.

The strange thing about Philosophy at Sydney in those days was that there were two departments of philosophy " the "Traditional and Modern", and the "General". These names revealed nothing: but they were worlds apart. General specialised in the more "political" forms of thought: feminist theory, Marxism (though not much after 1989!), the French postmodernists and the like. T&M, on the other hand, was a more blokey affair, teaching logic, epistemology, moral philosophy, and the much derided "dead white males." It was clear that one department believed in the actual process of thinking, while the other had by and large reduced all forms of thinking to "power."

I was not corrupted by philosophy - in the end probably because I didn't attend sufficient classes. (I was corrupted by the Evangelical Union instead" ). In second year I chose English and History and left Philosophy behind.

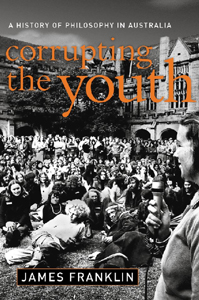

James Franklin's Corrupting the Youth, however, narrates the fascinating history of this world into which I had been barely initiated. The story of philosophy in Australia is a turbulent one. Some very good philosophy has been produced along the way; but there have also been the disastrous episodes of bitter division, parochialism, group-think and attempts by church and state to do what Athens did to Socrates.

At the centre of the story is the colossal figure of John Anderson, the Scottish-born Challis Professor of Philosophy at the University of Sydney from 1927 to 1958. Anderson's philosophical stance was once summarized by James McAuley in these terms:

John Anderson had an answer to every conceivable question. It was "No". (p.1)

Anderson was at heart (like Socrates) a critic. He relentlessly attacked moralism of all kinds, promoting a severe kind of realism (it goes without saying he was a committed atheist). He was a thinker to be reckoned with, in a city with not many serious thinkers.

Yet he had his faults. Though the severest of critics, he was not himself to be the object of criticism. He published comparatively little, and wrote with little reference to scholarly debates going on elsewhere. But he gathered around him generations of students who fell under his spell. He inculcated in them an "Andersonian orthodoxy", discouraging his students even from expanding on his thought in their own work. His disciples, as they matured, recognised that his refusal to take criticism of his own position seriously was an intellectual flaw (p. 47).

And it was his influence on the young that governments and church leaders perceived as a threat. But to all attacks Anderson was impervious. When publicly attacked by Anglican Archbishop Hugh Gough, Anderson replied:

The academic world has to attack any religion which tries to lay down requirements not in accordance with reality. In any university the fight between secularism and religion is intense " church-going minds are childish. We are dealing with people who are not really adults. (p. 99)

Anderson's affair with a student is an unsavoury part of Anderson's life that Franklin narrates. He goes on to chart Anderson's influence on the next generation of Australian philosophers " the developers of "Australian materialism" - and freethinkers, including the (in)famous Sydney "Push".

Franklin presents the history of his topic with an impressive balance (and wealth of sources), though he becomes much more polemical towards the end of his book when addressing the excesses of the postmodern-cultural studies fad. His sympathies, when they appear, lie with the revival of scholastic Catholic philosophy. It is certainly interesting how seriously Australian Catholics have taken philosophy over the years: Sydney Anglicans cannot point to a sustained development of a philosophical position in the same way.

I get the feeling that Franklin is not against "corrupting youth" per se, except when it is done by bad thinking. He will have no truck with the prevailing skepticism towards Absolute Truth and the human self and provides several examples of the worst kind of verbal sludge that parades for academic prose in contemporary academe. It was this species of thinking that led to the famous Sydney University schism in the 1970s, when students were allowed to mark their own papers and even first-years could vote on new appointments. (These things were no longer true by the late 80s alas!). The two departments finally reunited in 2000, but not, in Franklin's opinion, to any good end. He writes gloomily:

Since the other universities in Sydney have never taken philosophy very seriously, Sydney is no longer a city where a student can find a respectable course of study in philosophy. (p.312)

If this is true, then more's the pity. Our society needs people who are trained in good thinking.

Michael Jensen lectures in Church History and Theology at Moore Theological College in Sydney.