“Almighty God, we call upon you for . . . an outpouring of your Holy Spirit upon us . . .”

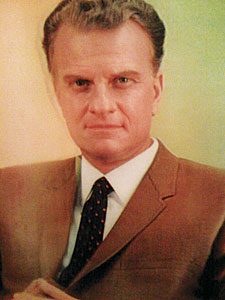

So begins the current Mission Prayer of the Diocese of Sydney. Do you believe that God will answer it? More than 40,000 fervent members of 5,000 prayer meetings in 1959 believed that God would answer such a prayer. They prayed that, when Billy Graham came to town, Sydney would experience "the greatest moving of the Spirit of God' that it had ever known. By the end of the second week of the Sydney Crusade, Graham observed that he had never witnessed such a response to the Gospel. ‘Spiritual hunger is the greatest I have ever known in my ministry,’ he said, ‘This is the work of the Holy Spirit.’

Did this work of the Spirit amount to a genuine revival? How did it impact evangelicalism in Australia? And why was Billy Graham's preaching so unusually effective in 1959? Those are the three main questions I will address.

Did the Southern Cross Crusade bring revival to Australia?

The Southern Cross Crusade took in Australia and New Zealand. Nearly 3.25 million people attended meetings, 25 per cent of the entire population of both nations. Of these 150,000 decided for Christ. In Melbourne, where the Crusade began, attendances totalled 719,000 with 26,440 enquirers for Christ, (3.7 per cent). Attendances at the Sydney Crusade totalled 980,000 with 56,780 enquirers, (5.8%. The highest response rate appears to have been in Tasmania (Hobart 6 per cent, Launceston 7 per cent). The average response rate of 4.6% of his hearers for the whole of Australasia was more than double Graham’s average response rate which is 2 per cent. (by 1989, 2m out of 100m).

The Southern Cross Crusade took in Australia and New Zealand. Nearly 3.25 million people attended meetings, 25 per cent of the entire population of both nations. Of these 150,000 decided for Christ. In Melbourne, where the Crusade began, attendances totalled 719,000 with 26,440 enquirers for Christ, (3.7 per cent). Attendances at the Sydney Crusade totalled 980,000 with 56,780 enquirers, (5.8%. The highest response rate appears to have been in Tasmania (Hobart 6 per cent, Launceston 7 per cent). The average response rate of 4.6% of his hearers for the whole of Australasia was more than double Graham’s average response rate which is 2 per cent. (by 1989, 2m out of 100m).

The first thing seen by a visitor to the Billy Graham Center, based for 50 years in Minneapolis, is a picture of the Melbourne Cricket Ground, packed with 143,000, the largest crowd ever to occupy that hallowed space. Never have so many Australians been so interested in the Gospel. But was it a revival? Graham never insisted that it was a revival. He declared that it was necessary to wait for 30 years before making such a judgement. So, in 1989, at the 30th anniversary, I judged that it was! My detailed argument is found in chapter 7 of my Evangelical Christianity in Australia.

In summary, revival may be defined as a powerful work of the Holy Spirit, poured out on large numbers of people at the same time, bringing them to repentance and faith in Christ. It is usually preceded by a heightened expectation that God is going to do something remarkable, by unprecedented unity among Christians, and by extraordinary prayer. It is always accompanied by the renewal of the church, the conversion of large numbers of unbelievers, and the reduction of sinful practices in the community.

Five of those characteristics are easily illustrated in the case of the Southern Cross Crusade. We have already noted evidence of extraordinary prayerfulness and of the conversion of large numbers of people.

Detailed statistical analysis reveals that, contrary to trends, the consumption of alcohol fell in the year immediately after the crusades; the rate of increase of illegitimate births was slowest in the same year; and there was a reduction in overall crime indices. Not many spiritual movements have had that effect in Australian history. It is an effect consistent with revival.

We all hope for the success of "Connect09', reaching out into unchurched communities. But there was no doubt that "Connect59' was a great success in that it did engage the respectful and hopeful interest of many people outside the church. And many outside the church were so transformed by the message that the whole community was blessed with a reduction in sinful, criminal and anti-social behaviour.

Also consistent with revival is the unprecedented unity enjoyed by the churches immediately before the Crusade. By 1959 Billy had already turned his back on the sectarianism of fundamentalism. He was not concerned to dwell on what divides Christians, convinced that in Church history ‘the great divisions have always resulted from somewhat minor differences.’ He believed ecumenical pragmatism essential to evangelistic success, and his team adopted a policy of harnessing the support of all the clergy, rather than offend any of them.

Not all clergy accepted the welcome. Among Anglican bishops, E. H. Burgmann of Canberra and Goulburn, T. B. McCall of Rockhampton, and T. T. Reed of Adelaide, condemned the Crusade as dangerous mass hysteria. But Billy’s growing friendship with a number of senior Anglican clergy "” Clive Kerle, Marcus Loane, Archie Morton, Leon Morris, S. B. Babbage, Archdeacon Arrowsmith "” goes a long to explaining the success of the Australian crusades.

The unity between Sydney and Melbourne evangelical Anglicanism was also a very important, perhaps critical factor, in the success of the Crusades. Melbourne had more lay experience in evangelistic enterprise and was thus well-placed to initiate the grand campaign; Sydney had more strength to carry the battle higher and further.

And revitalisation of the churches?

Churches everywhere recorded dramatic increases in attendance. Some were very dramatic: 325 inquirers were referred to Holy Trinity, Adelaide, and 646 to St Stephen's Macquarie Street, Sydney, the latter purportedly a world record at the time. 404 were added to the membership of St Stephen's. About three years later, both churches reported that seven out of ten were continuing in their new-found faith.

Anglican and Presbyterian data shows growth in the years that followed. Methodist numbers peaked in 1962. But, not surprisingly, the denomination which benefited most from the Crusade were the Baptists. Billy Graham is a Baptist, and Baptists traditionally are enthusiastic about evangelistic campaigns to increase membership. It is also known that, whereas the proportion of decisions at the Crusade approximated to the denominational strength in the wider population in the case of Anglicans, Methodists, and Presbyterians, the Baptist percentage of decisions was five times higher than that of its percentage of the population. With about 2% of the population the Baptists scored 11.6% of the decisions, exactly the same percentage as the Presbyterians who had 10.7% of the population.

As for heightened expectation, it seems that no-one expected that it would be as successful as it was. All the plans and projections were exceeded. But there were signs for those with eyes to see. There were numerous unusually successful parish missions in Sydney Anglican churches in the 1950s. In 1956 Canon Loane, then Principal of Moore College, and later, Archbishop, predicted that revival was coming to Australia: there were ‘signs of the chilly winter air beginning to yield to a warm and sunny springtime’.

Significantly, expectation was found outside the church, especially in the media. Billy’s concern for national regeneration was appreciated by the national press, reflecting a desire for revival then found in the wider Australian community. In early 1959 an editorial in the Melbourne Age observed:

The most significant and arresting feature of the evangelistic crusade that is being launched upon the Australian people is the obvious fact that, in its preliminary and preparatory stages, it has demonstrated a passionate desire on the part of widely differing sections of the community for a revival of true religion comparable with the great revivals of history.

All six characteristics of historic revivals were fulfilled in the Southern Cross Crusade. It was the closest Australia has come to "The Great Awakening'.

Impact on evangelicalism?

The Crusade's converts included many future church leaders. If the evangelical churches of Australia were weakened between the wars by the decimation of its future leaders in World War I, they were strengthened from the 1960s by the conversion of many prominent leaders in the Southern Cross Crusade.

Peter and Phillip Jensen and Bruce Ballantine-Jones are well-known Sydney Anglican examples.

Many leaders, already with an appetite for evangelism, became far more accomplished and confident evangelists, buoyed by the evidence of mass conversion, and trained in new skills and attitudes. In particular, counsellor training for the Crusade prepared lay people for a more active role in their churches, and their ministers were more inclined to use them. For their part, lay leaders were more inclined to work through their churches.

Theologically, the Crusade seems to have had a marked effect on Australian evangelicalism, which was now more confident than ever in its leadership of Australian Protestantism, wresting the initiative from the liberals.

For the most part, evangelicalism before '59 was perhaps too inward looking in its Pietism and defensive in its fundamentalism, rather than evangelistic. Billy's example reversed that.

Furthermore, the Bible was again widely accepted as the Word of God. Billy’s uncompromising refrain, "The Bible says', did more for the reestablishment of the Bible’s authority than the defences of the fundamentalists.

The theology of the Diocese of Sydney " evangelistic, Bible-based " had received in one short visit, a resounding endorsement.

What can we learn from Billy's preaching?

My brother, David, was converted at the '59 crusade, leading to a domino effect of conversions throughout our family. We lived in the country, and David was the only member of our family to attend the Crusade. Little did I know that almost thirty years later, I would have the opportunity to visit the Billy Graham Center at Wheaton, Illinois, to study the copious records of this remarkable event which had such an impact on my family and the whole nation. The archives hold films and videos of his crusades. I listened to many of the sermons he gave in Australia in 1959.

I did not hear one of those sermons without crying. Not so much because they were emotional " had I been at the '59 Crusade as a young teenager, I doubt I would have cried. Not many people cry at Billy Graham Crusades. They rather hear him in silence, a deep, reverent silence as the films of the Crusade reveal so strikingly.

No, his sermons were not emotional. But they were just so perfect. Graham was at the height of his powers in Australia in '59. His gospel presentation was so straightforward, crystal clear, simple " simply magnificent. It was their perfection which made me cry.

In spite of the tears, I managed to take notes on the anatomy of a Billy Graham sermon to see if I could understand the reasons for its perfection. Billy looks for five things in every sermon he preaches:

1. Comprehension

2. Conviction

3. Confession

4. Cleansing

5. Challenge

Perhaps Billy Graham's preaching has been as effective as it has (high response, high rate of permanence in the commitment, considerable contribution from his converts to the betterment of this suffering world) because he looks for all five results from his preaching.

The intriguing question, of course, is why are not other preachers as effective as Billy Graham? Might it be that they have largely ignored 1 and 5 above? Might it be that that some preachers are not more effective because they rarely get beyond 1? Might it be that the Holy Spirit especially anoints the preaching of this man? He does seem especially gifted at preaching this simple Gospel. Thus the perfection.

Attempts at analyzing perfection usually fail. Any who heard a Billy Graham sermon in 1959 will probably think my analysis here has not achieved much. Sermons are expressions of God-formed character. They are not words written; they are words spoken.

As an historian I would say that the great sermons of the past are better studied in films than in books, and I am grateful for that experience of watching Billy Graham preach evangelistically so perfectly in 1959.

Dr Stuart Piggin is director of the Centre for the History of Christian Thought and Experience and Senior Research Fellow in the Department of Modern History, Macquarie University. He is author of Evangelical Christianity in Australia (OUP, 1996).

photo: Mike Monteiro