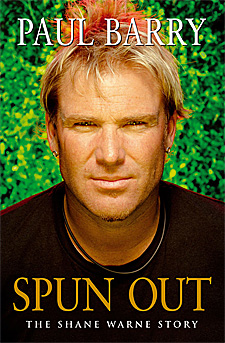

"He is a walking paradox they say. He is supremely confident yet profoundly insecure. He is brilliant but also a buffoon. He is generous and thoughtful, but utterly self obsessed." So begins Paul Barry's 541-page book about Shane Warne.

There has been an explosion of sporting books of the sort, "My Life in Cricket (or Tennis or Football) ... As Told To', but "Spun Out' is no ordinary sporting book either in length or the manner in which the author approaches his subject. Nor is Paul Barry an ordinary sporting newspaper hack regurgitating old newspaper clippings.

A graduate of Oxford University, he won the prestigious journalist Walkley Award in 2001, has worked for the BBC, the ABC, Channel 7 and 9 and The Sydney Morning Herald. The subjects of his books include such prominent people as Alan Bond and the media moguls the Packers and the Murdochs.

Barry's primary interest is not to simply chronicle Shane Warne's cricket achievements, but to turn his binoculars beyond the cricket field to examine why Warne is the paradox he is.

Barry's primary interest is not to simply chronicle Shane Warne's cricket achievements, but to turn his binoculars beyond the cricket field to examine why Warne is the paradox he is.

Furthermore, because sport is not played in a vacuum and is an integral part of Australia's social development, Barry explores why society in general and the cricket world in particular have mostly tolerated Warne's "misdemeanours'. More importantly Barry's insights into Australian culture are relevant to any who would want to interpret the word of God to everyday Australians.

Warne's headmaster at Mentone Grammar, described Shane as a person who "did what he wanted and never thought about the consequences". Barry, in this no-holds-barred wrestle with Warne's personality, takes us through the major "scandals' of Warne's life. His "sacking' from the Australian Cricket Academy, his incessant infidelity, his Graham Richardson "whatever it takes' approach to sledging batsmen, his taking money from a bookmaker for information and his taking of a diuretic are all documented.

However, this is not a voyeur's ride. Barry analyses the decision makers involved in these events and the community's response to the participants.

Barry leaves us in no doubt what he thinks of Warne's off-field behaviour. He calls Warne an idiot, labels his extra-martial sexual liaisons as stupid and says Warne's personal life teeters between tragedy and farce. But why does Barry call Warne's behaviour into question?

Principally because it does not conform to the traditions or the rules. The reasons Barry gives for opposing sledging is that older cricketers see it as a cancer on the game and that it is a far cry from the traditional genteel game of the past. His reason for condoning the popping of fluid reducing tablets " it's against the rules. Of course, for Christians these parameters are insufficient.

Sport has been and remains one of Australia's most important social agencies. Of the past nine Australians of the Year four have been sports people. Sports people get state funerals; poets, painters, opera singers and authors don't. Barry concurs. He writes, "Australia sees absolutely no problem in telling its cricketers they are like the diggers who fought at Gallipoli, because sport defines the nation. We engage in it with warlike intensity".

Christians ought not to agree with this philosophy but we should understand it if we want to share Christ with our cricket worshipping, sports loving nation.