John Carroll, professor of sociology at La Trobe University, Melbourne, is not afraid of big ideas. His 2004 book The Wreck of Western Culture " a substantial reworking of a 1993 effort " is a passionate, daring and sustained attack on the bloodlines of what we call "the West." He calls his book "a spiritual history of the West." He writes with a refreshing polemical zeal and with none of the hedging and over-qualifying so characteristic of academic prose.

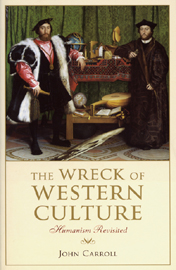

Carroll's claim is that "humanism" " by which he means the intellectual and cultural movement originating in the Renaissance " has had its deficiencies exposed in the latter-day collapse of western culture. Most particularly, the humanist belief in the supremacy of the human free will as alternative to obedience to God has been revealed as self-defeating " not least by the devastating symbolism of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The strategy Carroll employs for demonstrating this thesis is a selectively genealogical one. In a deliberate snub of postmodern orthodoxy, he examines some of the finest works of high culture in the humanist half-millennium: Hamlet, Holbein's The Ambassadors, Rembrandt and Poussin, Mozart and Kant, Kierkegaard and Nietzche, the novels of Henry James and the films of John Ford. It is an idiosyncratic choice and an unorthodox method, which Carroll justifies because these exceptional masterpieces have "tapped the deepest truths of their time" (p.9). His interaction with these works is stimulating and masterful and makes The Wreck of Western Culture a pleasure to read.

Crucial to the history Carroll traces is the famous sixteenth century debate over the freedom of the human will between the doyen of European humanism, Erasmus of Rotterdam and the German reformer Martin Luther. Carroll bravely reads Luther as more anti-humanist than anti-Roman Catholic. The irenic Erasmus was a reasonable man. If there is no human free will, he argues, why should the wicked reform? But Luther's teaching of justification by faith alone meant a complete rejection of this reliance on human will and reason. For Luther, the human being is a slave to sin and sentenced to death; and must come, empty-handed, to the cross of the crucified Christ. Mere morality was a hopeless absurdity. The heart of the Protestant reformation, rooted in the writings of Paul, is an acknowledgement of the helplessness of the human as a result of sin and death and a need for absolute dependence on God. Humanism, with its alternative diagnosis of the basic goodness of human beings and their freedom to be moral, leads inevitably to the rejection of God. There are some mealy-mouthed versions of Christianity that espouse this kind of thinking, even today: but the calamities of history must be held up against them as evidence. Man has proved a very poor god; ultimately death still undoes him.

Luther's insight is as crucial today as it ever was. What Protestant - in other words, Biblical - Christianity offers is a radically different diagnosis of the human condition. The humanist vision has been played out in full and now offers no comfort to the human soul. Carroll offers his work as a contribution to the funeral of humanism (p.268), with a warning for us not to give it another run.

But what does he offer as an alternative? Carroll enjoins the West to start again, to reach back into the past and recapture that right "enthusiasm for man and his works that the Renaissance attempted to enshrine" (p.266). He means by this a simple delight in place of the infatuation with the human that has bought us so badly undone. Carroll writes: "The culture of the West will not be renewed until the moment it kills Luther's monster [ie death], and once again achieves a death of death" (p.267). For Carroll, it is in the art of Poussin that a particular alternative is indicated. Though the Frenchman Poussin was a Roman Catholic, Carroll claims that in his pictures he was able to represent Luther's great ideas. He, too, sees "darkness where the light of neither law nor reason shines" (p.70). He, too, sees the necessity for life and hope to come from outside sources and to be recognised as gifts. Yet he differs from Luther, writes Carroll, in that he appeals to a radically different divinity " "the sacred breath moving through the mythos" (p.71).

At this point I confess Carroll loses me somewhat, and a bit of precise writing on his part might have helped. Suffice to say that he reads the great works of culture as reflective of "the body of timeless, archetypal narratives that carry the eternal truths: the big stories on which every culture is founded, ones that are then told and retold to each coming generation" (p.70). It is in this mode that he considers theology, art, literature and philosophy: they are the things that a culture needs to survive, what Carroll has called in a previous book our "dreaming".

An exciting feature of Carroll's work was his determination to take theology seriously and to read Luther and Calvin as major thinkers in the history of the West (which indeed they are). However, Carroll hangs back from a thoroughgoing endorsement of them, or from charting a clear alternative course for the Western person. But that is not his intention: this book is ground-clearing rather than ground-breaking. Further, I would have been fascinated to see Western culture compared with Eastern or Islamic cultures. Are these less "wrecked" than ours? Admittedly, Carroll does briefly consider the clash of civilisations through the lens of the 9/11 conflict.

In any event, Carroll's work is a full-blown challenge to the decadent culture we inhabit, a culture trying ever harder to assert a basic human goodness but everywhere having to deal with the destructive consequences of our will-to-power.

Michael Jensen lectures in Church History and Theology at Moore Theological College in Sydney.