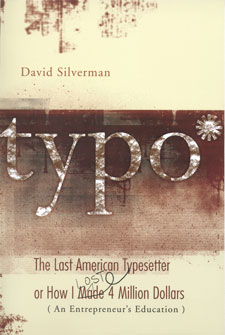

Typo, a memoir about buying a typesetting company is "amusing, appalling, infuriating and wonderfully written according to The Wall Street Journal'. Writing the story of a business flop is certainly not grist for the mill in the world of business where stories of the making of personal fortunes are more likely fare.

This is more than the story of a business failure. Rather, it's a cautionary story of the collapse of one man’s dream, told with personal honesty, insight and wry humour. The book is aptly subtitled "The Last American Typesetter or How I lost (overwritten on “made”) four million dollars: An Entrepreneur’s Education'.

Typo tells the true story of 32-year-old David Silverman’s purchase of the Clarinda Typesetting company using his father’s funds. The book chronicles Silverman's taking on and ultimately losing the entirety of the funds, his attempts to run a company which eventually flounders under the weight of shifting staff loyalties and their intransigence, a partner who was a closet alcoholic, outsourcing to cheaper labour markets and ever-changing fickle markets.

Typo tells the true story of 32-year-old David Silverman’s purchase of the Clarinda Typesetting company using his father’s funds. The book chronicles Silverman's taking on and ultimately losing the entirety of the funds, his attempts to run a company which eventually flounders under the weight of shifting staff loyalties and their intransigence, a partner who was a closet alcoholic, outsourcing to cheaper labour markets and ever-changing fickle markets.

On reflection, Silverman somehow manages to become philosophical about the situation realising that he kept the company going on sheer force of will for a year as well as accomplishing much. He comments that what upset him the most was his father not being able to see him succeed in business. He wanted to be “the best son I could be” to please his father…and also Dan, his business partner/father figure (who, as it transpired, was contributing to the business’ downfall with his alcoholism).

Typo also tells of his strained relationship with his father over the years. Unfortunately there is no “happy ending ” there either. His father dies before any real reconciliation is achieved, as does Dan, both of them severely affected by long-term alcohol abuse.

Sections of the book are prefaced by simple financial diagrams that detail his debt, revenue, customers etc, and their ever-diminishing status. The book does use some typesetting jargon but is nevertheless clearly comprehensible to the reader who may have no publishing background.

Silverman ponders the “what ifs” and whether he could have stopped the demise of the company or whether it was, as his partner stated, “watching the circus from the best seat in the house”. He realises, in hindsight that, given the factors at the time of a severe change in the industry that it was an “un-survivable perfect storm”.

The story is sobering and poignant in the telling but not maudlin. Silverman is, in every way, a realist and that “benevolent capitalists” rarely exist. After all, as Silverman states “capitalism is about making money”.