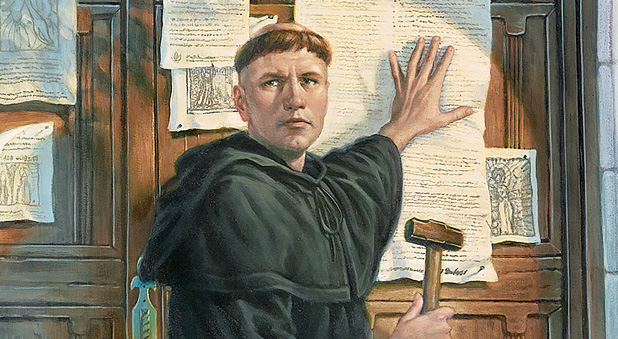

On October 31, 1517, in a small provincial town, an Augustinian monk who served as a professor in the university nailed a document to a church door. It started a revolution. Today, 500 years later and on the other side of the world, that unexceptional act – there would have been lots of notices on that door, since it was the unofficial notice board for the university – still captures the imagination.

More books are written about Martin Luther every year than about any other figure in history save one – the master he served, the Lord Jesus Christ. He was born the son of a copper miner in 1483 and grew up in an ordinary German family, but he was serious and studious and soon preparing for a career in the law.

Luther’s father Hans had great plans for his son. Martin would not struggle the way he had struggled. He would make his mark in the world. Hans Luther had no idea of the mark his son would make as Martin entered the University of Erfurt in April 1501!

The younger Luther’s life took a dramatic turn in 1505 after he finished the first stage of his studies. Caught in a violent thunderstorm and afraid for his life, he cried out for a saviour promising to become a monk if St Anne rescued him. Hans was furious – he kept muttering things about the fifth commandment. But Martin was determined. He had made a vow and he was duty bound to honour it. So, on July 17, 1505, he entered the monastery at Erfurt, expecting to be a monk for the rest of his life.

“I was a pious monk,” Luther wrote, “and so strictly did I observe the rules of my order that I may say: If ever a monk got to heaven through monkery, I too would have got there.” He conscientiously confessed his sins over and over again. He prayed. He attended mass. He did all the menial tasks – cleaning latrines, scrubbing the floors – all of it. Later he would say, “This is the chief abomination: we had to deny the grace of God and put our trust and hope on our holy monkery and not on the pure mercy and grace of Christ”.

However, only five years later, Luther’s father confessor announced that Luther was to do more study in order to lecture at the new university in Wittenberg. Luther would spend the rest of his life in that provincial town, radically transforming the university curriculum, then the church, and eventually Europe.

He began there as a Professor of Bible in 1512 and only left that post when he died in 1546. And rather early on was 1517 – the year that sparked the revolution.

The catalyst

One of the things Luther did as a university professor was write, and publishers could not get enough of it. He wrote with passion and an unshakable conviction in the urgency and truth of what he had to say. And in 1517, two pieces he wrote signalled a dramatic change.

The first, in September, was the Disputation against Scholastic Theology. This was his great break with the dominant way of writing and teaching theology in the medieval church. Luther systematically dismantled the foundations of what had been taught in the universities and schools for centuries. “Hope does not grow out of merits,” he insisted, “but out of suffering which destroys merits.” In other words, you cannot secure your own future. You cannot earn your way into God’s favour, or even contribute to it. God must save us, from beginning to end. The publication caused a stir immediately. Theologians all over Europe were furious.

Then Luther published his Disputation against the Power of Indulgences, better known as The 95 Theses, on October 31 – the date celebrated as Reformation Day ever since. The very first of the theses set the tone: “When our Lord and Master Jesus Christ said, ‘Repent’, he willed the entire life of believers to be one of repentance”.

“It is vain to trust in salvation by indulgence letters,” Luther wrote, “even though the indulgence commissary, or even the Pope, were to offer his soul as security.” The piece of paper promising your release from purgatory in return for payment, or the release of someone you love from purgatory, again in return for payment, was worthless. And, perhaps most famous of the 95, thesis 27: “There is no divine authority for preaching that the soul flees out of purgatory the moment money clinks in the bottom of the chest”.

Those in Rome immediately saw Luther’s theses as disputing the power of the Pope and they went on the attack at once. He had to be silenced or his writings would unravel the cords by which ordinary people were bound to the ministry of the priest and the Pope’s authority. Luther was not just criticising abuses – this had been done before. He was challenging the theology that undergirded the abuses, which was dynamite and they knew it.

Luther’s impact

The 95 Theses were read all over Europe. Lives were changed. Patterns of thinking, patterns of church life, patterns of community and family life, even patterns of government – all changed. Luther put the Bible at the centre of church life in the place of tradition; the family at the centre of a Christian community’s life in the place of the monastery; Christ the Saviour at the centre of Christian devotion in the place of Mary, the saints and Christ the Judge.

He translated the Bible into vernacular German in 11 weeks and transformed the German language in the process. He created the model pastor’s home when he married Katherina von Bora in 1525.

Yet Luther was certainly no saint. Fiercely intelligent without a doubt, but generous with those who opposed him? Not at all. His language could be extreme, as in his writing against the peasants in 1525 or his later writing against the Jews in 1543. It is hard not to be offended as you read those tracts today. I wish he had had never written them. But the most venom was always reserved for the Pope and the Roman church.

Peasants may have courted anarchy, that terrible work of the devil. The Jews had not converted en masse as Luther thought they would when the gospel was recovered. But the Pope had robbed God’s people of their greatest treasure, profited from misery and taught false doctrine that enslaved those for whom Christ died. “The Pope is the antichrist”, Luther concluded – the instrument the devil uses to pollute the world and oppose God’s work in the gospel. He didn’t mince words when he was angry. And sometimes the language was foul.

Luther’s courage

Yet there were wonderful moments of extraordinary courage, when all the odds were stacked against him. Of these, his stand before the Emperor, the princes of Germany and the officials of the Roman church at the Diet of Worms in 1521 was most remarkable.

The appearance at Worms had been anticipated for months. The Pope had given strict instructions that Luther was not, under any circumstances, to be allowed to give a speech. The Emperor was determined this upstart monk must be silenced.

All the way to Worms Luther was shaking. He did not fear death, but feared most of all that when it came to the test he would buckle. He feared the devil would win. On the appointed day he entered the room and there was a table laden with his books and tracts. He was taken to examine them and led to his place. Two questions and only two questions were to be put to him and he was instructed to answer simply “Yes” or “No”.

“Are these your books?” Of course they were. They had his name on them, after all. “Will you recant?” This was the question everyone had been anticipating. The princes leaned forward in their seats. And then Luther, who knew very well how to milk a moment for all it was worth, asked for 24 hours to consider the question.

You can imagine the sense of anticlimax. You might imagine the frustration and the anger at this manoeuvre. After all, hadn’t he expected precisely this question? Shouldn’t he have been prepared? But the extension of time was granted, though not without a few barbed comments from the Emperor.

The next day Luther was again led into the room. The table was still there, and the books. “Are these your books?” “Yes.” “Will you recant?” At which point Luther astonished everyone by questioning the questioners. “But you do not want me to recant them all, do you? They are not all the same. There are three kinds of books here. Some of them are devotional works, on the creeds and the Lord’s Prayer. No one says anything against those books. You don’t want me to recant them, do you?”

There were those written in the heat of debate, he continued, and perhaps he had spoken too harshly in those. But the others were simply explanations of the teaching of the Bible, on grace and Christ and the gospel, and no one had yet shown him that they were wrong. “If I am shown they are wrong from Scripture, then I’ll gladly recant. But no one has done that yet.”

It was a masterstroke. He had found a way to give a speech and to make his case. His enemies were furious. “Yes or no,” they screamed. “Yes or no!”

And that’s when Luther did it. That’s when he said, “Since then your serene majesty and your lordships seek a simple answer, I will give it in this manner… Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the Scriptures or by clear reason (for I do not trust either in the Pope or in councils alone, since it is well known that they have often erred and contradicted themselves), I am bound by the Scriptures I have quoted and my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and will not retract anything, since it is neither safe nor right to go against conscience. I cannot do otherwise. Here I stand. May God help me. Amen.”

The official stenographers didn’t get the last few lines. Pandemonium had broken out in the hall. Luther was taken out by friends, drained but rejoicing that he had come through the test. On the way home he would be kidnapped by his own prince in order to keep him in safe custody in the Wartburg, the castle just outside Eisenach. By then he was both excommunicate and an outlaw.

Luther the theologian

The Luther story is full of high drama. A German theological professor in a small, new and little-known university, trembling and fearful, had upset the entire world. And the consequences are still felt today. And it began in 1517 when he called teachers and students back to the Bible, away from sterile philosophy and scholastic folly, and when he called men and women back to a life of repentance and faith in response to God’s extraordinary mercy.

Luther has been co-opted for all kinds of projects since his own time. He has been the proto-German nationalist, the forerunner of Marxism and communism; the first historical critic of the Bible, the man who would challenge that criticism on the basis of the Bible’s own message; one of the great exponents of introspection and despair, the man who pointed us beyond ourselves to a work done for us first and only then in us.

He was a statesman, counsellor, educator, guide and musician. But he was always, first and foremost, a theologian who taught about Jesus from the Bible. He changed language, politics and society but that is not what he set out to do. He wanted to talk about God and the great thing he has done by giving his Son so that the guilt we like to pretend does not attach to us, our estrangement from the God who made us, our corruption and pollution, and our enslavement to desire and to the devil and his schemes, might be dealt with completely and forever.

I recently heard the suggestion that the Reformation should be summed up simply in the words “freedom” and “responsibility”. Luther himself would have used a single, very different word, for he was all about Christ. His preaching was about Christ. His lecturing was about Christ. His writing was about Christ. His counselling and everything else was about Christ.

Luther didn’t just insipidly endorse the values of our culture or his own. He challenged us all with Christ. What have you done with Christ? Have you laid aside your self-importance and self-preoccupation and taken hold of Christ? That is what Luther’s reformation was about from beginning to end. Everything else was, and is, die Mache – window dressing.

This is an edited version of an address given by the Rev Dr Mark Thompson at the opening of the Luther exhibition at St Andrew’s Cathedral, August 2017.