“I’m always surprised by how someone like myself has maintained the centrality of Christ for how one thinks theologically, and I think that is more a reflection of the people that have supported me than any personal achievement.”

Coming from someone like Professor Stanley Hauerwas, Professor of Theological Ethics at Duke Divinity School in the United States, that statement is at once surprising and yet somewhat familiar. This is, after all, the man who once quipped in an essay that, “We stand under the word because we do not believe we have minds worth making up on our own."

So it’s perhaps not surprising to find that kind of idea levelled at himself, a man with hundreds of publications and a 30-year faculty position at Duke under his belt.

“The centrality of Christ will not win you accolades from the world today, and as an ambitious academic, that doesn’t necessarily pay off,” says Professor Hauerwas, speaking to Anglican Media Sydney. “I’ve had a wonderful life, though, and I’m deeply grateful for that.”

It is this very centrality that Professor Hauerwas has brought to bear on his perspective on politics and ethics, in particular, and is one of the defining aspects of his work. For Professor Hauerwas, theology and the person of Jesus Christ at the heart of theology, do not merely give a view on ethics and politics. They are themselves an ethic, a politic, and so the life of a disciple, and of the church, is to be characterised by those things at a fundamental level, and not in reference to the framework and beliefs of a secular world.

Professor Hauerwas, in Sydney to give the Annual Lectures at the University of New South Wales’ Anglican residential New College, says the key idea he most wishes to convey in them is that the ‘how’ and the ‘what’ of Christianity are inextricable from each other. The activity of Christian faith is itself a core part of that faith.

“For example, the Gospels are fundamentally manuals of discipleship, so you cannot separate christology from what it means to be a disciple of Christ,” he says. “They are mutually interdependent, and so the 'how' is a way of suggesting that Christianity is not beliefs plus actions that come from those beliefs, but our most fundamental convictions are forms of activity, of ‘how’. That's crucial for understanding what it means to say, 'what we believe is true'."

The series of three lectures take root in Professor Hauerwas’ own development as a theologian. Even still, he’s not above taking another wry look at himself and one of the reasons he took the lectures in the direction he did.

“I’m 73. I’ll be dead before I know it,” he laughs. “And, well, I thought it was probably a good time to time for me to try to think thoughts I once had, only differently, in the hopes that I could better understand what I’ve thought. I think that’s a useful exercise for any theologian to engage, because we theologians have to say more than we are. That’s what I’m trying to understand.”

The lectures conclude on Thursday.

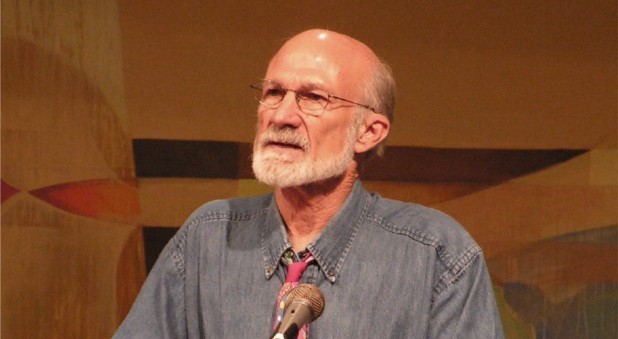

Image: Jordan Cooper, under Creative Commons