The common view that women report depressive symptoms at higher rates than men can lead us to assume that women have a certain vulnerability to depression or that men are comparatively healthy.

However, when depressive symptoms reported by women and men's statistics on drug and alcohol abuse and suicide are taken into account, the statistical difference narrows. There seems to be an inextricable link between what men "feel' and what men "do' when they are depressed which may help to explain why depression in men is often hidden.

This article reports on findings from a major study examining men's experience of depression. The findings will equip men to detect, and act on, symptoms of depression in themselves and in others.

The "Big Build'

The men in the study were able to observe common symptoms of depression including feeling tired or lethargic, restlessness, being fidgety, agitated, irritable, indecisive, overwhelmed, having problems concentrating, stomach upsets, change in sleep patterns, changes in weight, or unexplained aches and pains or complaints.

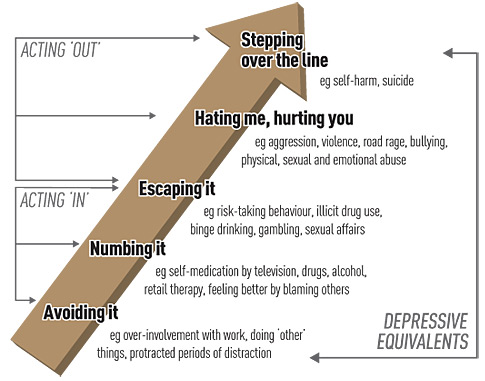

In addition to these symptoms they reported that some men who are depressed are likely to socially withdraw, use avoidant, self-medication and escape behaviours, and use violence, aggression, and suicide to alleviate the symptoms.

Analysis and interpretation of these findings have been conceptualised in a trajectory of emotional distress, labelled The "Big Build' [see diagram]. The "Big Build' is a play on words that depicts men's outer strong physical appearance and an internal intolerance and intensification of depressive symptoms that can be triggered by negative thoughts or events manifesting in anti-social behaviour.

Avoiding it

Withdrawing socially and avoiding problems can be useful and effective strategies in the short term while our brain processes information and problem-solves. Protracted periods of withdrawal, avoidance or denial can, however, delay resolution and make the problem worse. It can also exacerbate the pain of social exclusion by unwittingly or determinedly avoiding those who can effectively help.

Numbing it

Numbing or self-medication is intended to mitigate or soothe our pain. We enjoy feeling good and it is normal to feel good more often than not. We resist feeling pain and emptiness. We do this by, for example, watching too much television, using retail therapy, or drugs and alcohol. These artificial or temporary panaceas don't effectively deal with the problem. The problem doesn't go away. Delayed resolution can then lead to more serious behaviours and consequences such as drug and alcohol addiction.

Escaping it

Our propensity to escape from something threatening is useful. It is protective and keeps us from being harmed or killed. It helps, though, to understand from what or whom we are escaping " from danger, dread, adversity, conflict, being offended or hurt, or being alone or lonely, emptiness, contrition (guilt), responsibility or accountability. How we perceive the threat will determine how we respond to it.

Dangerous risk-taking behaviour such as road rage, binge drinking, gambling, sexual affairs or other behaviour that is out of character may signal underlying problems.

Hating me, hurting you

Intense emotions work to protect ourselves or to defend others. Anger can be used for good for the benefit of others. Rage and revenge are, however, a distortion of that emotion leading to abuse of power, violence, and aggression. Not all men who are depressed commit anti-social offences, and not all men who commit anti-social offences are depressed.

However, depression can be an intolerance to emotional distress which can manifest in anti-social behaviour usually with dire consequences, not only for men themselves, but for their victims.

Stepping over the line

Suicide is the ultimate escape: a desperate act from being overwhelmed towards release, relief, freedom from reason, and deceptive peace. It can also be an act of defiance, indignation, and ultimate objection to pain and suffering, fuelled by pride, and refusal to relinquish control. It can also be a result of enslavement, entrapment or torment. In any case, the longing for peace is misplaced, misdirected, perverted and distorted.

What is unique about the "Big Build'

Depression is serious for both men and women, particularly for those suffering severe and persistent symptoms which demand appropriate therapeutic intervention.

However, the perception of depression as a "feminine' problem can be fuelled by social conditioning of men (by men and women) to suppress emotional distress and signs of weakness ("boys don't cry").

Social norms that make it easier for women to admit to experiencing depression can make it difficult for men to admit to it. There remains a conflict in men between the individual need to express emotion and social constraints not to.

Depression in men can, therefore, be misunderstood, misrepresented, misinterpreted, misdiagnosed, mistaken or misread as "men behaving badly'. The "Big Build' is a new and clinically recognised approach to identifying symptoms of depression in men that would otherwise remain hidden.

What use is the "Big Build' to churches/Christians?

Depression is hidden even in the church (the body of believers). Men in the church, from pulpit to pew, are not exempt from the ravages of depression nor are those indirectly or vicariously affected simply by sharing their lives with men who are depressed or "at risk' of depression. It is more problematic when depression confers a stigma and carries a misconception in that Christians should not get depressed.

Depression is hidden even in the church (the body of believers). Men in the church, from pulpit to pew, are not exempt from the ravages of depression nor are those indirectly or vicariously affected simply by sharing their lives with men who are depressed or "at risk' of depression. It is more problematic when depression confers a stigma and carries a misconception in that Christians should not get depressed.

Yet Christians, more than most, should expect adversity in all its different shapes and forms but at the same time should be equipped, with the help of God's Spirit and helpful others, to actively manage and deal with it. The Christian marathon is both an individual pursuit (we are responsible and accountable for what we do with Jesus Christ, and our relationship with others) and a team effort as we help each other over the hurdles and obstacles (adversities that threaten to trip and defeat us) and to spur each other on towards The Goal.

Are men today any different in their emotional distress to men centuries ago? In centuries gone by, negative emotions were described with words like despair (2 Corinthians 1:8), distress (Psalm 18:6), downcast (Luke 24:38), sorrow (2 Corinthians 7:10), mourning (Nehemiah 1:4), remorse (Matthew 27:3), and misery (Hosea 5:15). Nehemiah sat down and wept when he heard that the wall of Jerusalem was broken down, and its gates had been burned (Nehemiah 1:4).

Job was bereft of his family, possessions, and his health. He said, "I have no peace, no quietness; I have no rest, but only turmoil' (Job 3:36). The Prodigal Son felt humiliation, remorse, and regret (Luke 15:11-32). David mourned for his son Absalom (2 Samuel 18:33). In the depths of his despair (Psalm 22), he kept turning to God with his anger, pain, suffering and questions, as did Job (2 Samuel 7:18; Job 42:1-6).

In the fullness of his humanity, Jesus expressed (righteous) anger (Matthew 2:16), he wept over his friend Lazarus (John 11:35), he felt compassion (Matthew 9:36), he became frustrated with his disciples (Matthew 8:26), he rebuked them (Mark 16:14), he often withdrew to lonely places to pray (Luke 5:16), he was overwhelmed with sorrow to the point of death (Matthew 26:38), and he called out to God in his anguish (Matthew 27:46; Luke 22:44). He suffered and felt the full brunt of the sins of the world, taking them to the Cross in our place (Mark 8:31; Isaiah 53:5).

God expresses anger (Psalm 95:10; Deuteronomy 7:4). He hates sin (Exodus 20:5). He detests pride (Isaiah 25:11). He is jealous (Deuteronomy 6:15). Yet, he loves us (John 3:16). Both his rod (discipline) and his staff (guidance and protection) comfort us (Psalm 23:4), for our good and for his purpose.

God expresses anger (Psalm 95:10; Deuteronomy 7:4). He hates sin (Exodus 20:5). He detests pride (Isaiah 25:11). He is jealous (Deuteronomy 6:15). Yet, he loves us (John 3:16). Both his rod (discipline) and his staff (guidance and protection) comfort us (Psalm 23:4), for our good and for his purpose.

Emotions are God-created and God-given. We know the joy of good news, the pleasure in giving, the relief from tension, the sadness or grief of separation, and the anger of injustice. If we didn't experience the depths of despair and hopelessness, we would not know joy and hopefulness.

Pain is a gift, both physical and emotional " it tells us we are alive. It lets us know that something is wrong, or right, which demands a decision, an action and a momentum, resulting in a consequence for ourselves and for others. At their best, emotions produce creativity and maintain and sustain life. At their worst, emotions can lead to destructive, vengeful and violent behaviour towards others and the self.

Yet, the emotion that drives us to escape "from' pain is the same emotion that drives us "to' the need for forgiveness and healing. The emotion that drives us to hate is the same emotion that drives us to love and be loved (the opposite being indifference). The emotion that thrusts us toward despair and suicide is the same emotion that yearns for ultimate restoration, reconciliation and hope. Despair of all the things of this world is the same emotion that points us to trust in Christ alone. [1]

Pain is realised in our emotions. It is not intended to harm or destroy us. Our response should not be to avoid, numb or escape the pain, but to understand the reason for our emotional response, and to stand firm (Ephesians 6:13; 1 Corinthians 16:13; 1 Corinthians 15:58).

The "Big Build' is a diagrammatic representation of a series of defeats, rather than victories, in the battle between flesh and spirit (John 3:6; Romans 8 and 9). In our need, pain compels us, then, to redirect our attention toward God, and to restore, renew, and reinvigorate our relationship with Him through Jesus Christ, the Author and Perfecter of our faith. We opt for a hopeless end or an endless hope. Hope does not disappoint. [2]

—————

[1] The Consolations of Theology Seminar Series, School of Theology, Moore College, 20-21st September, 2006.

[2] Romans 5:5.

Acknowledgement: To the men and women who have informed, and continue to inform, this work, my sincere gratitude.

Suzanne Brownhill BSW MPH PhD

Extracts from her doctoral thesis are accessible via Australian Digital Thesis and the publication Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 2005;39;10;921-931; and The Consolations of Theology Seminar series, School of Theology, Moore College, 20-21 September 2006.