"How's it going?"

It's a familiar question I get from my wife - female teen fiction isn't my normal genre of choice " as I wade through books that I wouldn't normally choose to read for the purpose of a review. I was tempted to roll my eyes in some parody of suffering, but it would have been just that, a parody.

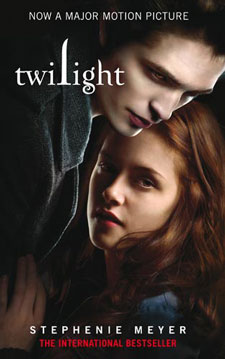

Twilight is surprisingly good, and the series' influence is likely to reach far beyond the high school-aged girls it is clearly aimed at. It's not just the clever writing, or the creative twist on an old fantasy character. The book succeeds in tapping into a very human ache for something far beyond this dreary world.

For those who haven't had time to catch up on this latest teen obsession, Stephanie Meyer's Twilight series tells the story of Bella, a teenage girl who moves from sunny Phoenix to the perpetually damp town of Forkes in Washington State to live with her divorced father. There, amongst the dark woods and down-to-earth inhabitants, she attends a new High School where everything is just that bit drearier than her previous home. Everything, that is, except for Edward, the youngest member of the pale but stunningly beautiful Cullen family. Edward, it turns out, is a vampire, though he and the rest of the Cullens have turned their backs on hunting humans, and now prey on animals of the forest instead. There are primal urges at work though, and as the relationship between Bella and Edward develops, he must constantly resist the urge to "fall off the wagon'. The story's dilemma sharpens as new vampires come to town, but the focus remains on the love-struck characters throughout.

For those who haven't had time to catch up on this latest teen obsession, Stephanie Meyer's Twilight series tells the story of Bella, a teenage girl who moves from sunny Phoenix to the perpetually damp town of Forkes in Washington State to live with her divorced father. There, amongst the dark woods and down-to-earth inhabitants, she attends a new High School where everything is just that bit drearier than her previous home. Everything, that is, except for Edward, the youngest member of the pale but stunningly beautiful Cullen family. Edward, it turns out, is a vampire, though he and the rest of the Cullens have turned their backs on hunting humans, and now prey on animals of the forest instead. There are primal urges at work though, and as the relationship between Bella and Edward develops, he must constantly resist the urge to "fall off the wagon'. The story's dilemma sharpens as new vampires come to town, but the focus remains on the love-struck characters throughout.

Well, no surprises there. It's aimed at teenage girls after all.

Twilight, the first volume in a four-part series, has a number of positives to recommend it. It is spectacularly successful in capturing the young female mindset and, as such, might be worth a read for parents wondering what is going on in their daughter's head. It demonstrates well the significance of gossip, "chats', outings and social connections for this age group. More importantly, through Bella, it reflects back to teenage girls the common inability to see their own beauty because of an over-concentration on what they cannot do.

Meyer is clearly very aware of the danger of obsession, particularly in relationships. She even uses Bella to warn against it on numerous occasions. Her character is aware that an inability to think straight in Edward's presence is not a healthy thing. Furthermore, the book does some very plain dealing with the topic of sex in the teenage years. Asked by Edward if she has ever been with someone, Bella makes it clear that in her mind there is nothing casual about sexual intimacy:

"Of course not," I flushed. "I've told you I never felt like this about anyone before, not even close."

"I know. It's just that I know other people's thoughts. I know love and lust don't always keep the same company," [Edward says].

"They do for me," [Bella replies].

There is also a strong sense that marriage is the appropriate path for couples who want to spend their life together, though whether or not sex waits for this is not so clear.

Many parents will probably baulk at the idea of their children reading such a series because of its connection with vampirism. For that reason, it is worth considering how Twilight deals with the subject. To begin with, Edward is unhappy that he is a vampire and does not wish that Bella should join his fate. It is an almost irresistible urge he fights against on a daily basis and one that he pleads with Bella to be sensible about, particularly in the way that her actions affect his ability to resist. Meyer treats vampirism more like an addiction, and I found myself constantly wondering if the characters would behave much differently towards each other were Edward a recovering drug addict or a victim of some other compulsive behaviour. Edward doesn't wallow in self-sympathy; he just asks for understanding:

"Just because we've been " dealt a certain hand " it doesn't mean that we can't choose to rise above " to conquer the boundaries of a destiny that none of us wanted. To try to retain whatever essential humanity we can."

To that end, the book serves as an interesting encouragement for people to "love the unlovely', and extend sympathy and support rather than condemnation towards those who are trying to do something about their situation.

"OK," you say, " but they are still vampires."

Yes, and that is part of the problem with Twilight, though it's not one that it has exclusively. The vampire has been rewritten in past years to become the rebel of the age. In all manner of books and films they live outside of normal society, are possessed of incredible abilities and you never see them badly dressed. The mythological concept of them being damned for all eternity as servants of the darkness has been quietly dropped. Twilight almost revives the gothic novel's approach to vampirism where the vampire was something of a romantic figure because of his tendency to creep into women's bedrooms at night and bite them on the neck.

The only reason that such a warped view of this sort of character can exist is because westerners have largely lost touch with real suffering. We generally no longer personally participate in the slaughter of animals or even the preparation of food. Blood is almost foreign to us and confined to fantasy contexts. Were we to see the life torn from any creature, particularly another human being, in such a violent way as a vampire suggests, we would soon discover the mixture of anger and sadness Jesus displays for death at the tomb of Lazarus. Meyer's books will only confirm this ignorance since every act of violence associated with her vampire characters is carefully edited, never to be witnessed by her first-person protagonist.

God does turn up briefly between her pages, though. Edward says he believes that it is far more likely that vampires, along with the rest of the world, are creations rather than accidents of evolution. Furthermore, his adopted father, Carlisle, was formerly the son of an Anglican minister. This ancestor is condemned because of his brutal attitude towards people he believed to be witches and vampires but, considering that he was literally attempting to protect his flock from being eaten, it's hard to muster much condemnation for Edward's charge of ‘intolerance'.

Probably the most valuable illustrations for Christian purposes, though, are Bella's constant assertions that there are things worth abandoning this life for. The book begins and ends with her conviction that, "Surely it was a good way to die, in the place of someone else, someone I loved." This is, in the end, the theme of the book. There are some things worth dieing for, and at the topmost motivation is the guarantee of someone else's life. That person doesn't even have to be that deserving of your sacrifice. What is crucial is how you feel about them. In that respect Bella finds herself in a number of occasions in the place of Christ, prepared to offer herself up to save others.

Dying to this world for the sake of something greater is Twilight’s basic message. Ecclesiastes tells us that God has placed a longing in every heart for something that this world does not contain; an enduring life that we know no earthly pleasure will satisfy. Bella is prepared to turn her back on the world she knows for an eternal life with Edward " one which others would definitely not understand " for the sake of their relationship. Once you have met someone you value above life itself, everything else is immaterial. It provides the obvious question for every parent of a teen reading Meyer's novel: have you met someone worth more than life itself?