On April 8 Justice Peter Jones of the British High Court finally brought down his judgment on The Da Vinci Code.

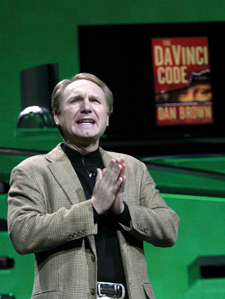

Dan Brown was being sued by Michael Baigent and Richard Leigh authors of a 1982 conspiracy-style expose of the Roman Catholic Church called Holy Blood and Holy Grail, for copyright infringement. They claimed Brown copied the plot of The Da Vinci Code from their book.

For many millions of fans around the world, Mr Brown's victory adds credibility to the "truth' of his historical claims. As The Sydney Morning Herald put it, "Both books explore theories " dismissed by theologians but embraced by millions of readers " that Jesus married Mary Magdalene, the couple had a child and the bloodline survives".

In fact, almost one in six North Americans now believe The Da Vinci Code's claims about Jesus are true. No doubt that figures in Australia would be similar. According to a CanWest news poll last month, 17 per cent of Canadians and 13 percent of Americans say Jesus Christ's death on the cross was faked and that he married and had a family.

When it comes to Jesus it seems the facts just don't seem to matter if an alternative theory "feels' more true.

For example the internationally reknown commentator (and usually sensible) Christopher Hitchens dismissed the boring historical facts about Jesus, to embrace the newly translated Gospel of Judas because he feels it just "makes more sense' of the Jesus story. (see fact box).

Pagans in the pews or emerging church?

One of the world's leading historians of early Christianity, N T Wright, says that he encountered the ideas found in The Da Vinci Code everywhere from theological colleges to local evangelical churches long before the novel was written. But that Dan Brown has "given these myths wings' and now "they are flying everywhere confusing people'.

Dr Wright has identified a number of historical myths, and says each of them are weaved together by The Da Vinci Code into its compelling narrative.

The key myths are:

Myth 1. There were dozens if not hundreds of other documents about Jesus. Some of these have now come to light, such as the books discovered at Nag Hammadi in Egypt 60 years ago, and they prove Jesus was a merely a great religious not a divine being.

Myth 2. Jesus did not think he was God's son, or that we would die for the sins of the world; but he did leave us some wonderful moral and spiritual teaching. He may well have been married, perhaps even with a child on the way, when his career was cut short by death.

Myth 3. The four Gospels were written centuries after Jesus' life to turn him into God, and so help the church in Rome claim power and prestige. They were selected for this reason, at the time of Emperor Constantine in the fourth century, who ruthlessly crushed alternative (pro-women) voices.

The conclusion drawn from belief in these myths is that Christianity as we know it is based on a mistake. For many people, it is also linked to a conviction that mainstream Christianity has a harmful view of sex and is particularly anti-women.

During his recent visit to Australia, Southern Cross asked Dr Wright, who is also Anglican Bishop of Durham in the UK, if he knew any churches that were engaged in successful mission to believers in these ideas.

Dr Wright found it difficult to cite any on-the-ground examples he could endorse.

However he added that the emerging church movement is certainly one attempt to reach those people attracted to the myths of post-modernity.

The emerging church is a nebulous movement, so it is hard to define. Nevertheless the response of our churches to this movement is the key ministry question of our time. No doubt some emerging churches have embraced a syncretistic form of spirituality. Evangelicals need to ask if aspects of this approach are a legitimate missional response to an unreached people group or whether the whole movement is simply too dangerous, covertly importing pagan ideas into our churches.

Historically there are four main reasons Dan Brown is wrong. Constantine could not have secured the power of the Papacy, let alone "invent' Christian belief in the Trinity.

1. Constantine was no pagan

In response to the claim in The Da Vinci Code that the "pagan' Constantine invented Christianity to solidify his power, John Dickson in The Christ Files counters that Constantine was "definitely Christian'.

It is certainly a fact that Constantine was baptised as a Christian, but more evidence is needed to knock this theory on the head. Think how difficult it is to reach definitive conclusions about the sincerity of contemporary political leaders when they claim a Christian conviction. Just such uncertainty has allowed some historians to maintain Constantine faked his belief in order to exploit the growing significance of Christianity.

However this theory has big holes in it.

In 300 AD, Christians were only about 10 per cent of the population of the Roman Empire, and they lived mainly in the Greek-speaking East. This was not really an attractive or overwhelming powerbase for Constantine.

A more sensible conclusion is that the Christian population was now too large to totally oppress. To understand Constantine's motivations it is important to recognise that his reign came on the back of a savage, decade-long persecution of Christians called the Great Persecution that had proved destructive and counter-productive. It is certainly clear from reading Christian writers from the period, such as the church historian Eusebius, that Christians saw Constantine as their champion who would end their sufferings. But contrary to the stereotype, Emperor Constantine did not make Christianity the "state' religion. He merely allowed Christianity to be tolerated along with a host of pagan religions. Nevertheless this was a huge step forward for the persecuted Christians.

Constantine's "religion policy' was certainly motivated by a desire to ensure peace and order in his realm. This is why he wanted the Christian Bishops to come to common agreement at Nicaea and end a doctrinal dispute over the Trinity.

As to be expected of a new believer, Constantine was very naive about doctrinal issues early in his reign. Like most Roman Army officers of the time, Constantine had been a devotee of the Persian sun god Mithras, which he initially connected with Christ "the son' of God. But as his Christian understanding grew he even took to preaching himself in later years. Constantine was baptised in 337 a few weeks before he died by the Bishop of Nicomedia.

The most compelling evidence of Constantine's Christian commitment was his decision to move the Imperial capital to the Christian heartland of Greek Asia Minor in 325. He decreed that no pagan temples would be built in his new city. Constantinople was conceived as a fresh start - a decisively Christian capital free of the old pagan influences.

2. Christians always believed in the Trinity

The historical record shows continuous belief by Christian communities in the divinity of Christ and a Triune God. (see timeline on right). Contrary to the myth, the number of New Testament texts accepted by church leaders actually expanded over time from the initial authorised Scriptures of the Gospels and Paul's letters. Difficulties arose around 150 when Gnostic opponents began forging gospels and attributing them to Jesus' companions such as Mary, Philip, Judas and Thomas in order to lend credibility to their own teachings.

Subsequent church leaders were understandably cautious about what writings they considered authentic setting up two tests, they had to be a) written by the first witnesses to Christ, and b) consistent with the authentic writings of Paul and the Gospels. The canon was not created by a powerful Emperor imposing legitimacy on a narrow subset of texts. In fact most Gnostic texts did not circulate widely and some were not even known to the Christian leadership.

3. The so called "Vatican' was a disintegrating, pagan ruin

The Vatican did not arrive for 500 years after Constantine. The strongest Christian communities were always in Greece and Asia Minor where the Apostle Paul's missionary efforts had been focused. The fact that the Greek East had become the cultural and economic heart of the Empire was one reason Constantine moved the Imperial capital there in 325.

Led by the Senators, Rome remained a stronghold of paganism, in vast contrast to Christian, Greek-speaking Constantinople. When the Visigoths stood before Rome's walls in 408, the Senate proposed pagan sacrifices and Rome's Bishop was powerless to complain.

After being sacked three times in 400s, Rome had become a living ruin, with public buildings falling into disrepair and the population plunging to 50,000 around 530 during the war between the Goths and the Empire. Rome would not have another visit from its Emperor until 663, when Constans II proceeded to strip the city of its metal, from buildings and statues, to provide armaments for use against the Muslim Arabs. Rome's humiliation was complete.

4. The Emperor never ruled all "Christendom'

The idea that the Bishop of Rome, even with the help of the Emperor Constantine, had the authority to impose a particularly theology on all Christians is entirely incorrect. In fact parallel church structures had existed in North Africa since Emperor Decian had persecuted all Christians in the 200s. These "Donatist' Christians of North Africa were faithful to the Bible and Trinitarian in belief just like their "Catholic' neighbours. They just did not recognise the authority of Rome, originally because they were suspicious of apostates who rejoined the church when persecution stopped. A century after Constantine, the great theologian Augustine sought imperial coercion to force them to rejoin Rome, but the Donatists thrived on in their Algerian homeland until wiped out by the Islamic invasions of the seventh century.

More significantly by the 300s a very large number of Christians lived outside the boundaries of the Roman Empire in Ireland, Armenia, Ethiopia, Persia, and beyond. These churches still exist today.

Furthermore, Rome's position as the most important ecclesiastical centre is often over-stated. In the early Christian centuries doctrine was approved by consensus, with the "dioceses' of Jerusalem, Alexandria, Rome and Antioch and from 320 AD the Patriarch of the Imperial capital of Constantinople having virtually equal status. The Bishop of Rome was undoubtedly the senior religious figure in the Latin Western Empire, as officially stated in 380 by Emperor Theodosius in the Edict of Thessalonica. But in this period the Bishop of Alexandria in the Greek East tended to be the key player in major theological debate. The Bishop of Rome did not even attend the Council of Nicaea which defined the Trinity.

Further reading:

Davidson, Ivor, The Birth of the Church (Baker Books, 2004)

Davidson, Ivor, A Public Faith (Monarch Books, 2005)

60 SECOND HISTORIES

Bible compiled

By 90 AD Paul's letters had been collected, and together with the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke they were being circulated as the authentic "canon' of Christian Scriptures. The earliest list of "authorised' Scripture that scholars have found dates from Milan in 170 AD. It is virtually identical to our modern New Testament except it excludes Hebrews, 2 Peter, 2 & 3 John and Revelation.

Trinity clarified

In the 170s, Athenagoras writes a work for Marcus Aurelius aimed at stopping his persecution policy called Plea for the Christians. This outlines Christian belief in one God, the creator of all things, who is "trios' in character. Tertullian's seminal work Against Praxeus written in 213 coins the term "Trinity' to describe the Godhead as "three persons' in "one substance'. The Council of Nicaea in 324 overwhelmingly re-endorses the Trinitarian position (of the Apostles) rejecting Arius' view that Christ was not fully God.

Origins of the papacy

Starting in 476 there was nearly a century of anarchy in Italy, as the (Arian) Goths and the (Trinitarian) Emperor based in Constantinople fought an ongoing war for the former Imperial capital. By 550 Italy has been turned into a wasteland and Rome into a ruin with just a few ten thousand inhabitants. Without ongoing Imperial oversight, the Bishop of Rome comes to fill a local political power vacuum, setting the foundation for the Papacy.