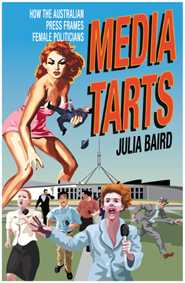

This book is an entertaining and informative critique of the Australian media's treatment of women who are prominent in politics. Former Sydney Anglican Synod member and Sydney Morning Herald writer Julia Baird is well aware that she has now joined the ranks of the very press that is under her microscope. But this doesn't hold her back in her quest to discover why, by and large, Australia's female politicians of all have promised much and delivered little. In part, Baird surmises, this is because of unrealistic expectations and invidious comparisons with figures like Margaret Thatcher.

The women that are her case studies are a roll call of burn-outs and has-beens: Cheryl Kernot, Pauline Hanson, Bronwyn Bishop, Natasha Stott Despoja, Carmen Lawrence, Ros Kelly. While each of these has made her own mistakes, the tales of their treatment at the hand of the media is indeed shameful. The pattern is predictable: first, the media darling, the female great white hope of Australian politics, "Australia's first female PM", perhaps; and then, after a period of time, the inevitable mistakes received with a mixture of glee and rancor that few male politicians ever experience.

Baird starts her narrative in the 1970s, when the first group of women politicians began to filter through into Australian parliaments. She records, with illustrations, how the media asked those women to pose with aprons on, or in front of the stove pulling out a roast. They are presumed to embody maternal, or feminine values: to be somehow more sincere or more gentle. The media " even female journalists and (especially) women's magazines - focuses undue attention on their appearance and their domestic and personal arrangements.

Why is this so? Here is Baird's explanation:

What drives a lot of the press coverage of female MPs is a questioning of their humanity. Those with right-wing views, who are not seen as particularly compassionate, are portrayed as almost subhuman monsters, with grotesque features ripe for satire or caricature " Bronwyn Bishop or Pauline Hanson. Those seen as honest, decent and warm-hearted are canonised and showered with praise for being human, real and like the rest of us " Carmen Lawrence, Cheryl Kernot, and even Natasha Stott Despoja" But then, when they show emotion, make mistakes, or behave like the men in playing political hardball, they are fiercely castigated.

We don't want them to play dirty like the boys. If they crack under the pressure, the ensuing criticism makes it clear we actually want them to be superhuman.

So: are women the victims of a prejudiced media? Baird insists not, and doesn't shy away from the mistakes the women themselves have made. Natasha Stott Despoja, for example, is portrayed as a woman who fanned the flames of media attention to her (then) hip, Dr Martens image, but then complained when she wanted to be taken seriously that no-one was listening. A new crop of female politicians " Julia Gillard and Amanda Vanstone, for example " have been successful in recent times by a more skilful handling of the media. This is at least in part because they are credible on policy issues; and because there is now more familiarity with female leaders.

So what do we want from our female politicians? Should we see them as contributing something different - "feminine" - to the government of our nation? Or should our expectations be exactly the same for them as for the men? These are not questions at the surface of Baird's book, but they are vital ones. It seems to me that there is a tension in our public discussions and portrayals of gender roles between celebrating the right to choose how to express one's gender and the fact that for human beings identity and gender are extremely closely intertwined. Women politicians still wanted to be treated as women, whatever that might mean. Part of the problem Baird exposes is that a complex discussion like this one isn't possible in Australia with the kind of media we have.

This book I think reveals more about the media than about women or feminism. From the perspective of this reader, the Australian media is more than positively disposed to feminism. My impression is that most journalists in print media write from within a paradigm of left-leaning secular liberalism which includes feminism and that is rarely challenged.

Despite this, the media deals in characters and conflict by lazily referring to a set of myths, clichés, images and stereotypes. Women politicians have scandalously been the victims of this laziness over the years: photographers trying to frame their image as "supermums" by picturing them in aprons. The point is: the bottom line in the media is not some ideological position but what makes a story of the kind that people want to read. Baird rightly doesn't argue that there is a conspiracy against women.

And yet, it is not just women in power who are prey to this banal shorthand. When I was asked to give a very short comment on a TV program earlier this year, I was specifically asked to wear clerical garb and to stand in front of stained glass, even though this doesn't accord with the reality of my life as a Christian and a minister or the style of services I attend. How is it possible to communicate through this fog of typecasting?

In reading Media Tarts I couldn't help reflecting on the portrayal of religions and religious figures in the media. I am sure a book could be written about how discussion of issues of faith is framed by a media according to its own version of how religion should be in society. It is assumed to be in decline. It is assumed that we are obsessed with certain issues of gender and sexuality. It is assumed that all we do is church politics. The total befuddlement of the media with the rise of the "values" issue at the latest election illustrates its commitment to its own paradigm and its inability to comprehend that which isn't easily caricatured. However, we church people have for our part made our mistakes, mainly by providing the media with a fascinating and ongoing conflict story and by forgetting to talk about Jesus.

However, Baird's message to women in politics ("How to succeed in politics without a penis") could be worth considering. There is no point in playing victim. The media is what it is; and like women in politics, Christians should learn to live with it. Flirting with it is dangerous.

Michael Jensen lectures in Church History and Theology at Moore Theological College in Sydney.